Embarking on the journey of game design presents two fundamental paths that an aspiring creator must walk. The first is the path of pure creation: starting with the spark of an original idea and meticulously building a new world, a new system, from the ground up. This is the act of invention, of bringing something novel into existence.

The second, and perhaps more foundational path, is that of analysis. This involves looking critically at the vast landscape of games that already exist—from ancient board games to modern blockbusters—and deconstructing them. What makes them work? Where do they fall short? What hidden structures lie beneath their surfaces? By learning to see games through this analytical lens, we develop the core capability this lecture explores: how to think like a game designer. We will focus on this second path, using analysis to sharpen our design instincts and build a vocabulary for creation.

The Essence of “Play”: An Invitation, Not a Command

At the very heart of game design is the concept of “play.” The English word itself is wonderfully ambiguous, covering everything from playing a game like Hopscotch to playing a musical instrument or watching a theatrical play. This linguistic breadth hints at a deeper truth: play is a mode of engagement. However, the crucial element that separates the play of a game from the passive consumption of music or film is interaction.

A game requires the active, voluntary participation of its players.

"You cannot force someone to play."

You can coerce them into going through the motions, but genuine play arises from an internal motivation, a willing acceptance of the game’s invitation. This is a vital lesson for designers. A game tested on a five-year-old provides immediate, unfiltered feedback; if the child is not engaged, they will simply walk away, offering a stark reminder that the designer’s primary job is to create an experience so compelling that players choose to enter and remain in the game’s world.

Play is not a monolith; it exists on a spectrum. At one end lies unstructured, emergent play, and at the other, highly structured, formal competition.

- Unstructured Play: Imagine children in a street, kicking a soccer ball. There are no fixed teams, no official goals, no referee. The rules are fluid, negotiated moment-to-moment. The objective is simply the joy of the activity itself.

- Structured Play: Now, picture a professional soccer match in a stadium. The rules are rigid and internationally recognized. The playspace is precisely defined. The goal—to score more than the opponent—is absolute. The play is competitive, strategic, and serious.

A designer has the power to move an activity along this spectrum by manipulating its core components.

The game of volleyball provides a perfect example. An indoor court match with six players per side is fast, powerful, and strategic. Move the same game to a sandy beach with only two players per side, and the entire dynamic shifts. The pace slows, movement becomes more difficult, and the strategies must adapt to the new playspace.

By changing a single element, the designer has created an entirely different experience, demonstrating that the “feel” of a game is a direct result of its design.

The Anatomy of a Game

If games are “machines that generate designed play,” then a designer must be an expert mechanic, familiar with all the core components of that machine. These elements are the levers and dials a designer manipulates to shape the player’s experience.

- Players: This is the most vital component. A designer must never forget they are creating for an audience. The digital storefronts are graveyards for thousands of games that were built without a clear player in mind, downloaded once and never played, or never downloaded at all.

- Rules: These are the formal constraints that create the structure of the game. They must be clear and convincing, compelling players to abide by them. The complexity of the rules directly influences the target audience; a game with highly intricate rules will appeal to a niche, dedicated audience, while simpler rules can attract a broader base.

- Playspace: This is the defined arena of play—be it a physical board, a digital screen, or an immersive virtual reality environment. The design of the playspace has profound implications for gameplay. Recall the early days of VR, where designers had to create contained environments (like a platform surrounded by a void) to prevent players from physically crashing into their real-world furniture. Modern AR, which overlays the game onto reality, presents new opportunities and challenges for playspace design.

- Objects, Actions, and Goals: These are the nouns, verbs, and objectives of the game. What can players interact with? What can they do? And what are they trying to achieve?

When a designer wishes to create a more open, playful experience, they will often intentionally de-emphasize the rigidity of the rules and goals.

A prime example is the collaborative drawing game, where the only "rule" is to extend small lines left by the previous player, and the only "goal" is the shared, often hilarious, reveal at the end. The joy comes from the creative process, not from winning.

The Designer’s Craft: Shaping the Space of Possibility

A game designer’s ultimate role is to create opportunities for meaningful play. They achieve this by constructing a Space of Possibility—the complete set of potential actions and experiences a player can have within the game.

This space can be vast and open-ended, as in sandbox games like Minecraft, which prioritize player freedom and emergent creativity. Alternatively, it can be narrow and focused, as seen in tightly scripted, narrative-driven games like The Last of Us.

In these games, designers often employ branching narratives to offer choices, but the sheer cost of developing unique content means these branches must eventually converge. A common technique to create the illusion of a wider possibility space is the use of optional side-quests, as seen in games like Fallout 4, which allow for player freedom without derailing the main, more constrained, narrative path.

A critical friction point arises when the perceived space of possibility does not match the actual one.

The game Detroit: Become Human illustrates this perfectly.

The game presents a stunningly detailed, bustling city, implying a vast world to explore. Yet, the player is often confined to an invisible, linear path. This disconnect between what the game promises visually and what it delivers mechanically can be intensely annoying, making the player feel tricked rather than guided.

The Game State—everything the game communicates to the player through its interface and environment—must therefore be an honest representation of the player’s true agency.

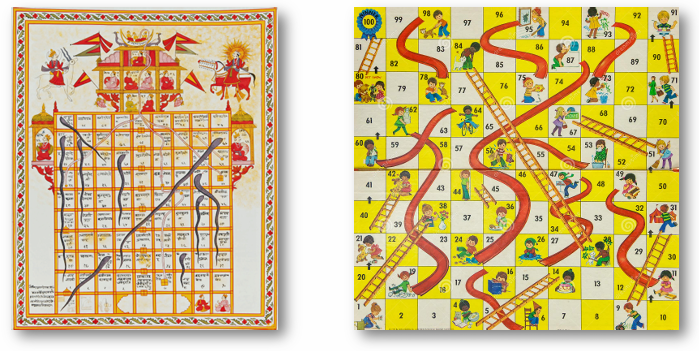

Deconstruction in Practice: Re-engineering Snakes and Ladders

To put this analytical thinking into practice, we can deconstruct a simple game like Snakes and Ladders. Originating in ancient India as a tool for teaching morality about karma and destiny, its core mechanic is one of pure chance.

The American version, Chutes and Ladders, reskinned this mechanic with a 1950s ethos of rewarding good deeds (like chores) and punishing minor misdeeds (like stealing cookies). Mechanically, however, the games are identical.

Analysis of the Base Game:

- Player Agency: Zero. There are no choices to make. The outcome is 100% determined by luck.

- Multiplayer Interaction: None. Players are engaged in parallel, individual races to the finish line. The social experience is external to the game’s system.

To evolve this into a more engaging experience for adults, we must introduce strategic depth by modifying the rules.

Design Interventions:

- Introducing Strategic Choice (Rules 1-3): By giving each player two pieces and two dice, and allowing them to split the dice rolls between the pieces, we instantly create a decision point. Do I advance one piece rapidly, or move both forward steadily? This simple change transforms the player from a passive observer of fate into an active strategist.

- Introducing Player Conflict (Rules 4-6): Allowing a player to use a die roll to move an opponent’s piece backward introduces direct, confrontational interaction. The ability to knock an opponent’s piece down a row by landing on it further deepens this conflict. These rules fundamentally change the social dynamic, opening the door for rivalries, temporary alliances, and a much more “nasty” but engaging game.

A seasoned game designer develops the intuition to foresee the cascading effects of such rule changes.

Finding the Game Beneath the Game

The card game Bartok serves as an excellent illustration of how game mechanics can be examined abstractly. The more common form of Bartok is a classic shedding-type card game, akin to Uno.

In its standard iteration, Bartok involves three to five players using a standard deck of cards (without Jokers). The objective is to be the first player to deplete their hand of five cards.

Gameplay proceeds clockwise, with players matching either the suit or the number of the top card on a discard pile. Failure to play necessitates drawing a card.

Critical analysis of a game like Bartok involves posing specific questions that probe its core mechanics:

- Difficulty Assessment: Is the game’s challenge level appropriately balanced for its target audience?

- Strategy vs. Chance: To what extent does strategic decision-making influence the outcome versus pure random chance? Games often exist on a spectrum, and understanding this balance is crucial.

- Meaningful Decisions: Does the game present players with interesting and impactful choices that affect the flow and outcome of play? Trivial decisions can lead to disengagement.

- Engagement During Downtime: Does the game maintain player interest even when it is not their turn? Mechanics like reactive plays or anticipating opponents’ moves can enhance this.

A key aspect of understanding game mechanics is recognizing how even minor alterations to rules can profoundly impact the overall experience.

Consider the proposed rule modifications for Bartok:

- Rule 1: Forced Draw (Playing a 2): This rule introduces a direct negative interaction, forcing the next player to draw cards and potentially skipping their turn. This increases the game’s difficulty and introduces a more aggressive strategic element, as players might hold onto ‘2’s for tactical advantage. It also enhances engagement when it’s not your turn, as players must anticipate and react to such plays.

- Rule 2: Match Card (Out-of-Turn Play): This rule injects an element of rapid, reactive play and turn manipulation. It drastically shifts the balance towards chance and quick reflexes, potentially making the game less about long-term strategy and more about immediate opportunities. It undeniably makes the game more interesting when it’s not your turn, as players are constantly vigilant for “match card” opportunities, though it can also lead to frustration from skipped turns.

- Rule 3: Last Card Announcement: This modification adds a social and memory-based element, penalizing players who fail to declare “Last card.” It increases the game’s difficulty by introducing a new condition to manage and shifts the outcome slightly more towards attentiveness and memory rather than pure card-playing strategy.

These examples demonstrate that altering a single rule can fundamentally transform the game’s feel, altering its difficulty, the interplay of strategy and chance, the significance of player decisions, and the level of engagement during other players’ turns. This iterative process of rule design and playtesting is crucial for designers aiming to evoke specific emotions or experiences.

Rigorous playtesting is indispensable for evaluating rule changes.

It is essential to conduct multiple playtests to ascertain an "average" experience and to guard against "flukes"—anomalous results caused by unusual card shuffles or other external factors.

Documenting such flukes is as important as identifying consistent patterns, as they highlight edge cases or unforeseen interactions that could still occur during regular gameplay.

The “Tunnel” Mechanic

Raph Koster’s perspective on abstract game systems is particularly insightful. In this simplified model,

a deck is divided into four piles, each concealing an ace. The player must sequentially flip cards within a pile until an ace is revealed, which then "unlocks" access to the subsequent pile.

This mechanic is a profound abstraction that Koster likens to Environmental Storytelling and fundamentally describes a “tunnel” system .

This “tunnel” mechanic operates on a simple yet pervasive principle: the player is confined within a specific segment of the game (the card pile) and must locate a designated “key” (the ace) to gain progression to the next segment.

This abstract model extends far beyond simple card games, representing a vast category of video game design paradigms where players navigate constrained environments, overcome specific challenges, or find particular items to advance to new areas or narrative stages. It emphasizes the sequential, often linear, progression driven by discovery and prerequisite fulfillment, stripping away all thematic elements to reveal the pure mechanical core of exploration and unlocking.

Example

- Gone Home maps perfectly to this. You explore one section of the house (a pile), looking for clues and keys (the ace) that grant you access to the next section.

- Even action games like The Last of Us follow this structure between combat encounters. The goal is to traverse a linear level (the tunnel) to find the “exit” that leads to the next part of the story.

Some of the most interesting games are those that take this familiar structure and subvert it. Spec Ops: The Line places the player in a typical military shooter “tunnel” but forces them into horrific, morally ambiguous choices that challenge the very nature of heroism in games. Far Cry 4 offers an even more radical subversion: at the beginning, the antagonist asks you to wait for him. If you simply put the controller down and wait, the game ends peacefully. You have the choice to reject the entire “game” of violence, a choice most players, conditioned by the genre, don’t even realize they have.

Shaping Philosophy and Expectations

Game definitions, though seemingly abstract, are fundamental to a game designer’s philosophy and directly influence a player’s expectations. These definitions are not merely academic exercises; they are powerful tools that shape the creative process.

In The Grasshopper (1978), Bernard Suits defines a game as

"the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles".

This broad, all-encompassing definition attempts to include diverse forms of play, from sports to make-believe. While it accurately captures the essence of a game’s structure, it provides little practical guidance for designers on how to create engaging experiences. Suits referred to make-believe as “open games,” defined by the sole goal of their own continuance, though he acknowledged that even these can have other objectives.

Game design legend Sid Meier famously stated,

"A game is a series of interesting decisions."

This definition says little about the semantic meaning of “game” but speaks volumes about what makes a good one. A decision is “interesting” when a player has multiple valid choices, each with potential positive and negative consequences, and where the outcome is predictable but not guaranteed. For Meier, the goal of a designer is to create a constant stream of these meaningful choices.

Jesse Schell, in The Art of Game Design (2008), defines a game as

"a problem-solving activity, approached with a playful attitude."

This definition emphasizes the player’s mindset, or what he terms the lusory attitude (from the Latin ludus for play, sport, and training). According to Schell, it is the player’s approach that determines if an activity is a game.

For example, two runners are in a race, but only one is "playing" if she views the race as a game, while the other sees it as a chore or a purely functional task.

In Game Design Theory (2013), Keith Burgun offers a more restrictive and precise definition:

Definition

A game is a system of rules in which agents compete by making ambiguous, endogenously meaningful decisions.

This definition is intentionally narrow to provide a clearer framework for designers. Burgun defines “ambiguous” as predictable but uncertain and “endogenously meaningful” as meaningful only within the context of the game’s system. This excludes activities like make-believe and pure competitions of skill, focusing instead on a specific, structured type of game.

Understanding these varied definitions is crucial for several reasons.

- Setting Expectations: A designer’s chosen definition helps them understand what a specific audience expects from a particular genre. A sports game, for instance, must align with a different set of player expectations than a role-playing game. Knowing the definitions of what constitutes a “game” in a given context helps designers craft experiences that resonate with their target players.

- Identifying the Periphery: These definitions provide a framework for understanding not just what a game is, but also what it isn’t. The “periphery” or “liminal space” between a defined game and other forms of media is often where new genres and innovative concepts are born.

- Professional Communication: Adopting a shared vocabulary based on these definitions allows designers to communicate more effectively with peers, theorists, and collaborators, fostering a deeper, more productive dialogue about the craft.

The most innovative designs often come from challenging these very definitions.

- Proteus challenges the need for goals, offering an experience of pure exploration.

- Button challenges the idea that rules must be enforced by a computer, creating a physical game where players must police themselves.

- Spaceteam breaks the “magic circle” by forcing its core gameplay—shouting commands—out into the real world, turning a digital game into a loud, chaotic, and hilarious social event.