The burgeoning field of human-machine interaction confronts us with profound ethical dilemmas that test the limits of our moral intuitions. A primary example is the programming of self-driving cars, which requires determining an algorithm for action in an unavoidable accident.

This raises complex questions of prioritization: should the vehicle protect its passenger at all costs, or should it prioritize the safety of pedestrians?

Further moral granularity is required when considering variables such as the age or number of individuals involved.

Similarly, the development of autonomous weapon systems, colloquially known as “killer robots,” forces a debate on the moral permissibility of machines designed to independently select and eliminate human targets without direct human oversight. A third area of ethical inquiry involves the creation of humanoid robots engineered to closely mimic human appearance and behavior.

These questions fall under the broader umbrella of the Ethics of Human-Machine Interaction, which can be examined from two perspectives:

- Design Ethics: How we should design machines and robots to behave around humans.

- User Ethics: How human beings should conduct themselves around advanced machines.

A critical point is that these “machines” are not simple tools, but entities empowered with advanced forms of AI, capable of learning, decision-making, and complex interactions.

Scope and Central Questions

To systematically address these complex issues, it is essential to delineate the scope of the ethical inquiry. The ethics of human-machine interaction can be broadly categorized into two fundamental lines of questioning.

- The first concerns the behavior of machines, focusing on how we ought to design artificial agents to behave ethically in the presence of humans, such as by programming a moral decision-making matrix for an autonomous vehicle.

- The second category pertains to human behavior, examining how humans should ethically conduct themselves when interacting with machines and robots, raising questions such as whether it is morally acceptable to abuse a robot that convincingly simulates the appearance and behavior of an animal.

It is important to clarify that within this discussion, the terms "machines" and "robots" refer specifically to entities equipped with advanced forms of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

The primary focus of this analysis is the interaction itself, with the central problem being to evaluate whether, and to what extent, traditional moral theories, conceived long before the advent of such technologies, can provide useful frameworks for navigating these contemporary ethical landscapes.

Moral Status: Agents and Patients

The applicability of traditional moral theories to the domain of human-machine interaction is contingent upon our conceptualization of the moral status of the entities involved. This necessitates a distinction between “moral agents,” who are entities capable of acting rightly or wrongly and can be held accountable for their actions, and “moral patients,” who are entities deserving of moral consideration and against whom actions can be judged as right or wrong.

This distinction gives rise to four potential frameworks for understanding the moral standing of humans and machines:

- Human-centric view: only humans are agents and patients. In this framework, the moral responsibility always traces back to the humans involved: the designers, programmers, users, and regulators. The machine is merely a tool.

Quote

“So let us stop talking about Responsible AI. We, computing professionals, should all accept responsibility now, starting with ACM!”

Moshe Y. Vardi (2023)

- Full moral status for machines: This view suggests that robots could achieve a status where they are both responsible for their actions and deserving of moral consideration. (often explored in science fiction).

- Artificial moral agents: robots as agents but not patients. This view proposes that machines can be designed to make moral decisions without having any moral status themselves. The field of Machine Ethics (Wallach and Allen 2009) argues for designing “artificial moral agents” precisely because they are functionally autonomous and potentially dangerous.

- Machines as patients: robots considered moral patients but not agents (Danaher, 2019), where they elicit moral duties despite lacking responsibility for actions. This view argues that robots are not responsible for their actions but may deserve moral consideration from us. The argument is that if machines behave like people or animals (entities we already view as moral patients), we should extend that consideration to them.

Limits of applying traditional theories

When turning to traditional ethical theories such as utilitarianism, deontology, and virtue ethics for guidance, two significant challenges emerge.

- Firstly, these frameworks were fundamentally designed as theories governing human-human interaction, with their core tenets and assumptions rooted in conceptions of human nature, consciousness, and social relations. Their direct application to human-technology interaction is therefore not straightforward.

- Secondly, there is a substantial risk of oversimplifying and decontextualizing these rich and complex theories when they are transposed into a modern technological context. These ethical systems evolved within specific historical and socio-political milieus, and importing them as simple problem-solving tools risks stripping them of their nuanced philosophical underpinnings and historical significance.

Case Study: the Self-Driving Car Dilemma

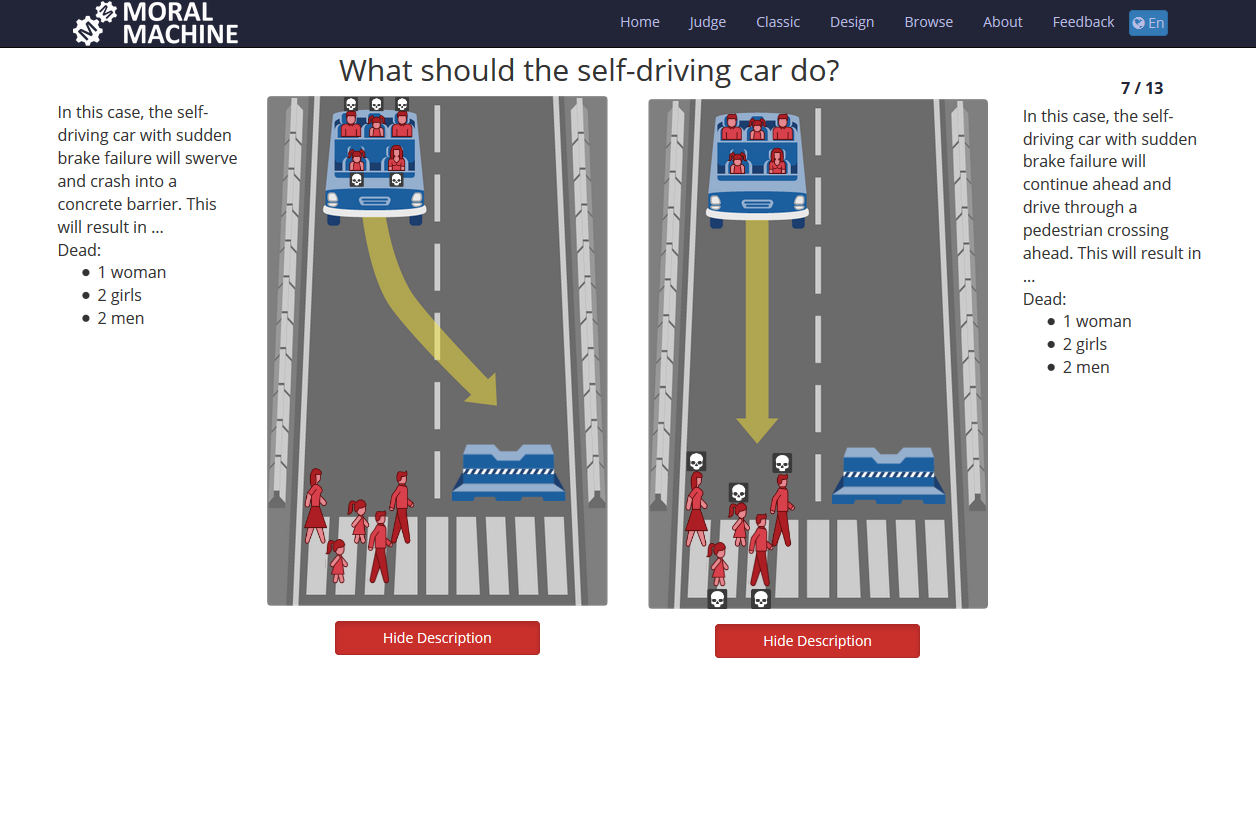

To illustrate the practical application of these theories, we can consider a classic moral dilemma involving a self-driving car with failed brakes. The vehicle must make an instantaneous decision between two outcomes:

- swerving into a concrete barrier, which would result in the deaths of its two occupants, or

- continuing straight and hitting three pedestrians who are crossing the road against the light.

While such extreme, high-stakes scenarios are useful for motivating the need to engineer moral agency and decision-making capabilities into machines, it is crucial to recognize that these dilemmas represent only a fraction of everyday ethical reasoning.

The true value of these thought experiments lies in how they connect to broader moral obligations and compel us to define the duties of a moral agent. Consequently, these are not merely abstract philosophical exercises; they have tangible impacts on critical design decisions and the life choices that are encoded into the systems that increasingly shape our world.

Modes of Moral Justification

Ethical reasoning is often structured around distinct modes of justification, which give rise to different families of moral theory. The three predominant approaches in Western philosophy are consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics.

- The first, consequentialism, judges the morality of an action based on its outcomes or consequences, with Utilitarianism being its most prominent form, focusing on counting and maximizing positive results.

- The second approach is duty ethics, or deontology, which posits that the morality of an action is inherent in the action itself and is determined by adherence to a set of rules or duties, regardless of the consequences.

- The third framework, virtue ethics, shifts the focus from actions to the character of the moral agent, emphasizing the cultivation of virtues and being a good person as the foundation of moral life.

Utilitarianism

Definition

Utilitarianism is a consequentialist framework in which the moral worth of an action is determined entirely by its contribution to overall utility, specifically the pleasure and pain it produces.

Its foundational axiom is the utility principle, which mandates that

the most ethical choice is the one that results in the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people.

This principle of maximization forms the core of utilitarian calculus.

The historical development of modern utilitarianism is largely attributed to the philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who articulated several of its core tenets. Bentham advanced a hedonistic view of value, asserting that pleasure is the sole intrinsic good, while all other goods are merely instrumental in its pursuit. Building on this, he formulated the utility principle as the primary guide for moral decision-making.

To apply this principle systematically, Bentham proposed a “moral balance sheet,” a conceptual forerunner to modern cost-benefit analysis, which involves weighing the aggregate pleasure (benefits) against the aggregate pain (costs) for each possible course of action to identify the most ethically sound option.

Criticisms of Utilitarianism

The critique of Utilitarianism, despite its appealing systematic structure, centers on several significant philosophical and practical dilemmas concerning the quantification of utility, justice in distribution, the treatment of minorities, and the inherent predictability of moral consequences.

The Problem of Quantifying and Comparing Utility

One of the foundational and persistent measurement problems in Utilitarianism is the inherent difficulty in objectively quantifying and comparing happiness or pleasure (utility) across different individuals. Classical Utilitarianism, particularly in the form espoused by Jeremy Bentham, sought to establish a “hedonic calculus” to measure intensity, duration, certainty, propinquity, fecundity, and purity of pleasure.

However, the subjective nature of these psychological states renders a truly objective, intersubjective metric practically elusive. For instance, the increase in utility an individual derives from a specific good is not directly translatable to the utility gain of another person, leading to problems in determining which action truly maximizes the aggregate sum of happiness, an essential step in applying the utilitarian principle.

Injustice, Minorities, and Rights

A profound moral criticism involves the potential for the tyranny of the majority and its subsequent implication for justice and rights distribution. Because the core principle of Utilitarianism is the maximization of total (aggregate) utility, it theoretically permits, and sometimes requires, the exploitation or sacrifice of a minority group if their suffering is outweighed by the vastly greater sum of happiness experienced by the majority.

This concern is often highlighted by counterintuitive endorsements, where actions widely considered morally abhorrent (e.g., punishing an innocent person to prevent a riot and maintain social order, or non-consensual organ harvesting if it saves five lives) could be theoretically justified under a pure sum-maximization calculus.

Furthermore, the theory is criticized for potentially producing an unjust distribution of costs and benefits; an outcome where the total utility is high, but the burdens fall disproportionately on a few, is permissible as long as the net sum is maximized, thus disregarding intrinsic fairness or equity.

Challenges to Predictability and Special Duties

The practical application of the theory is further complicated by the uncertainty of consequences. Utilitarianism, as a forward-looking, teleological moral system, presupposes the ability to predict the ultimate outcomes of various actions and their resultant utility with a reasonable degree of accuracy. In reality, the complex nature of human interactions and the myriad of potential, long-term effects of any decision often render this consequential prediction unrealistic or impossible, leading to moral decision-making based on probabilities rather than certainties.

Concurrently, Utilitarianism is criticized for the neglect of special duties and personal relationships. It demands strict impartiality, suggesting that an individual should regard the utility of a stranger as equally important as that of a close family member (e.g., a child or spouse). This impartiality can undermine the moral significance of obligations and duties that arise from personal relationships, commitments, and institutional roles (like contracts or promises), which are generally held as having prima facie moral weight independent of their immediate effect on aggregate utility. This suggests that the theory is often too demanding and conflicts with widely held moral intuitions about the role of personal ties and commitments.

Applying Utilitarianism to Human–Machine Interaction

The application of a utilitarian framework to the domain of human-machine interaction presents formidable challenges, particularly when considering the utilitarian calculus. The theory’s reliance on a quantitative, cost-benefit analysis necessitates a clear understanding of the causal chain between actions and their consequences. However, the digital environment is characterized by an unprecedented scale, complexity, novelty, and systemic interdependence.

Digital artifacts like advanced robots or global AI systems can produce cascading, long-term, and global consequences that are either fundamentally incalculable or can only be estimated based on highly speculative and questionable assumptions. While utilitarianism may function adequately in familiar, bounded contexts where outcomes are reasonably predictable, the high degree of uncertainty inherent in the digital realm raises profound issues for its practical application, undermining the very consequentialist foundation on which it is built.

When examining the moral status of artificial entities through a utilitarian lens, a clear distinction emerges based on the capacity for sentience. According to classical utilitarianism, the ability to experience pleasure and pain is the criterion for being considered a moral patient. Since machines and robots are generally understood to be incapable of such phenomenal experiences, their perceived “suffering” would carry no weight in the utilitarian calculus, and they would not qualify as moral patients in the same way that humans and other sentient beings do.

The question of moral agency is more complex.

- On one hand, moral agency can be straightforwardly assigned to the human programmers and designers, who bear the responsibility of creating machines that are configured to promote overall happiness and relieve suffering.

- On the other hand, the possibility of assigning moral agency directly to machines themselves remains a subject of intense debate.

The conditions under which an artificial entity could be considered a true utilitarian moral agent are not well-defined, but would likely involve the capacity to reliably and autonomously calculate and act in a manner that maximizes utility, a prospect that raises as many technical and philosophical questions as it answers.

Duty Ethics

Definition

Duty Ethics, or deontological ethics, is a framework that evaluates the morality of an action based on its conformity to a set of rules or duties.

The origins of these guiding rules are varied.

- They may be derived from Divine Command, where moral obligations are understood as edicts from a divine authority, such as those found in sacred texts like the Bible or the Qur’an.

- Alternatively, they may arise from a Social Contract, representing the implicit or explicit agreements that form the basis of a functioning society, as codified in laws or a corporation’s code of conduct.

- A third, and philosophically prominent, source is Reason, which posits that moral rules can be established through rational argumentation and are, therefore, universally applicable to all rational beings.

Kantian Theory: The Ethics of Duty and Reason

The most influential articulation of duty ethics was formulated by the Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). Kantian theory is predicated on several foundational principles designed to establish a moral framework grounded in pure reason.

A central tenet of his philosophy is the rejection of consequence-based morality. Kant argued that basing ethics on outcomes or the pursuit of happiness renders it contingent and subjective, as consequences are often unpredictable and individuals’ conceptions of happiness vary. He proposed that duty, as determined by reason, is the only valid and pure foundation for moral action. Central to this is the concept of autonomy, the capacity of a rational individual to legislate moral law for themselves through their own reason, rather than being governed by external influences or personal inclinations.

The Primacy of the Good Will

In his ethical works, Immanuel Kant posits that the only thing in the world that can be considered good without qualification is a good will. Other qualities that are typically valued, such as intelligence, courage, wealth, or even happiness, are only conditionally good. They can be used for malicious purposes if they are not guided by a good will.

For instance, an intelligent person can devise a cruel plan, and a courageous person can fight for an evil cause.

The goodness of a good will, however, is not derived from the results or consequences it produces. Even if a person with a good will fails to achieve their intended positive outcome due to circumstances beyond their control, the will itself remains intrinsically valuable. Its worth resides entirely in the act of willing, motivated by the right principles.

A crucial distinction must be made to fully grasp this concept: the difference between acting from duty and acting merely in accordance with duty. An action only possesses true moral worth, in the Kantian sense, when it is performed from duty. This means the motivation for the action is a pure respect for the moral law itself, simply because it is the right thing to do.

In contrast, an action performed in accordance with duty may be externally correct, but it is motivated by some other inclination or self-interest.

For example, consider a shopkeeper who gives correct change to all customers.

- If they do so because they believe honesty is a moral duty, they are acting from duty, and their action has moral worth.

- However, if they give correct change only because they fear that a reputation for dishonesty would harm their business, they are acting merely in accordance with duty.

While the action is the same, the underlying maxim is rooted in self-interest, not respect for moral law, and therefore, for Kant, it lacks genuine moral worth.

The Categorical Imperative and the Reciprocity Principle

The supreme principle of morality in Kantian ethics is the Categorical Imperative, a universal and unconditional command of reason from which all specific moral duties are derived. Kant articulated this principle in several formulations, two of which are paramount.

The first is the Universality Principle:

"Act only on that maxim which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law."

This formulation serves as a logical test for the morality of an action. An individual must first identify the “maxim,” or the subjective principle, underlying their intended action. They must then ask whether it would be possible, without generating a logical contradiction, for this maxim to be adopted universally by all rational beings.

For instance, a maxim of making false promises to secure a loan cannot be universalized.

If everyone were to adopt this maxim, the institution of promising would collapse, as no one would trust any promise made. The very act of making a promise would become meaningless, thus revealing a “contradiction in conception” that renders the action morally impermissible.

The second key formulation is the Reciprocity Principle, often referred to as the Humanity Formulation:

"Act as to treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of any other, in every case as an end, never as a means only."

This principle underscores the intrinsic worth and dignity of all rational beings. It forbids the instrumentalization of people, prohibiting us from using them merely as tools to achieve our own objectives. While individuals frequently engage with one another as means to an end (e.g., a customer interacting with a shopkeeper), this formulation insists that we must simultaneously respect their status as “ends in themselves”—autonomous beings with their own rational projects and inherent value.

Criticisms and Refinements of Deontology

Despite its profound influence, Kantian ethics is subject to several significant criticisms.

A primary objection concerns its rigidity in situations involving conflicting duties. The framework provides no clear procedure for resolving dilemmas where two or more absolute duties are in opposition.

For example, the duty not to lie may conflict with the duty to protect an innocent person from harm, as famously illustrated by the "inquiring murderer" thought experiment. Kant's insistence on the absolute nature of certain duties can lead to conclusions that seem intuitively immoral.

Critics also challenge the claim that all moral laws can be neatly derived from the categorical imperative into a perfectly consistent system, arguing that the ambiguity and complexity of real-world moral problems defy such a systematized approach. Furthermore, the deontological focus on rules is often criticized for its “blindness” to consequences. A rigid adherence to a moral rule, such as a strict prohibition on child labor, could lead to devastating outcomes in certain socioeconomic contexts if it displaces children into even more perilous situations like starvation or crime without providing a viable alternative.

Prima Facie Norms

In response to the absolutism of Kantian deontology, the philosopher W.D. Ross developed the concept of prima facie norms in 1930. This approach offers a more flexible, pluralistic form of duty ethics.

Definition

A prima facie norm is a duty that is considered binding and obligatory on its face—such as duties of fidelity, justice, or beneficence—but which can be overridden in specific situations by a more pressing moral obligation.

This framework acknowledges that moral life often involves conflicts between duties and requires that we employ our considered moral judgment to determine which duty takes precedence in a given context.

For instance, rather than an absolute prohibition on all child labor, a prima facie norm might establish a more fundamental duty that "children should not be forced into slavery or prostitution."

This creates a robust moral foundation while allowing for the contextual nuance required to navigate complex ethical dilemmas.

How can the Kantian Framework be Applied to Human-Machine Interaction?

When applying the Kantian framework to the domain of artificial intelligence and robotics, the central concepts of duty and obligation encounter a significant hurdle concerning the status of the machine. A foundational question arises: can an artificial entity, such as a self-driving car, be subject to moral evaluation through punishment, blame, or even sentiments like guilt?

Within the stringent confines of Kantian ethics, the answer is unequivocally negative. Morality and the duties it entails are predicated on the possession of practical reason, autonomy, and a “will” capable of self-legislating the moral law. As machines lack these intrinsic capacities for rational deliberation and autonomous choice, they cannot be held accountable for their actions. They operate according to programmed algorithms, not from a sense of duty derived from reason. Therefore, since a machine cannot possess a moral obligation, it cannot be considered a moral agent.

The Locus of Moral Responsibility

Following this logic, Kantian ethics also precludes machines and robots from being considered moral patients in the same manner as humans.

Moral patiency, or the status of being an entity toward whom moral duties are owed, is granted on the basis of rationality and the inherent dignity that comes with being an end-in-itself. Because machines lack these properties, they are relegated to the status of objects or tools. Consequently, the locus of moral responsibility does not reside within the machine itself.

The duty to respect others and to act according to universalizable principles falls squarely on the human actors who create, program, and regulate the technology. The designer who codes the vehicle’s accident-response algorithm, the engineer who builds the system, and the policymaker who sets the legal framework for its operation are the true moral agents. It is their maxims and actions that are subject to moral scrutiny under the Categorical Imperative, as they are the ones making decisions that impact the dignity and autonomy of other human beings.

Values and Norms

This discussion of ethical responsibility naturally brings forth the related concepts of values and norms.

Definition

- Values are understood as enduring convictions regarding what is worth striving for, such as justice, safety, or freedom. They can be categorized as either intrinsic, meaning they are valuable in and of themselves (e.g., happiness, autonomy), or instrumental, meaning they are valuable as a means to achieve another end (e.g., money).

- Norms, in turn, are the prescriptive rules that operationalize these values, specifying what actions are required, permitted, or forbidden. For example, the value of public safety is realized through norms like traffic laws.

The value of privacy is a particularly salient topic in computer ethics. While it is often justified on instrumental grounds—that is, privacy is valuable because it protects individuals from potential harm—a more robust argument, advanced by philosophers like Deborah G. Johnson, posits that privacy possesses intrinsic value. This view connects privacy directly to the Kantian ideal of autonomy.

Since autonomy is a fundamental component of human dignity and a prerequisite for moral agency, privacy becomes a necessary condition for its realization. The erosion of privacy through pervasive surveillance or data collection poses a direct threat to this core value. It creates a “chilling effect” that can alter individual behavior and discourage the free expression and deliberation essential for an autonomous life, thereby undermining the very foundation of personhood.

Future Directions

In summary, a direct application of traditional duty ethics to human-machine interaction leads to a clear and consistent conclusion: human beings remain the exclusive moral agents and patients.

The ethical responsibility for the actions of AI and robotic systems lies not with the artifacts themselves but with their human creators, owners, and regulators. However, this traditionalist conclusion is not the only available path. An alternative line of inquiry seeks to explore how machines might, in the future, acquire some form of moral status. This requires moving beyond the established frameworks of Kantianism and utilitarianism.

Scholars like Mark Coeckelbergh have advocated for exploring non-traditional ethical theories to address these new technological realities. One prominent alternative is the Relational Turn, which proposes a significant shift in perspective: instead of grounding moral status in an entity’s internal capacities, such as reason or consciousness, this approach focuses on the interactions and social relationships that form between humans and machines. From this viewpoint, a machine’s moral significance is not determined by what it is intrinsically, but by the role it plays in a social context and how it is perceived and treated by human beings, opening up new possibilities for conceptualizing the ethics of human-machine interaction.

Virtue Ethics

Definition

Virtue ethics is a normative ethical theory that prioritizes the concept of character over the adherence to rules or the consequences of actions. At its core, it posits that a virtue is a stable disposition to act and feel in particular ways, constituting an excellent or praiseworthy character trait.

These virtues can be broadly categorized into two types.

- Moral virtues are dispositions of character acquired through habituation and practice, such as courage, temperance, justice, and generosity. They govern our actions, emotions, and desires.

- In contrast, intellectual virtues are excellences of the mind, such as wisdom, understanding, and prudence, which are typically developed through teaching and learning.

While a societal value like honesty might be widely endorsed, the concept of virtue is more profound; it concerns the internalization of that value to the extent that it becomes an integral and consistent part of an individual’s character, informing their perceptions, choices, and actions for the right reasons.

The Aristotelian Foundation

The most influential framework for virtue ethics was established by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle in his work, The Nicomachean Ethics. Aristotelian ethics is fundamentally teleological, meaning it is concerned with the ultimate end or purpose (telos) of human life. For Aristotle, this ultimate end is eudaimonia, a term often translated as “happiness” but more accurately understood as “human flourishing” or “living well and doing well.” Eudaimonia is not a transient subjective feeling but rather an objective state of being, achieved through a lifetime of activity in accordance with reason and in fulfillment of our human potential. It represents the highest good for human beings, and it is realised through the consistent exercise of the virtues.

A central tenet of Aristotle’s ethical system is the Doctrine of the Mean. He proposed that

every moral virtue is an intermediate state, or a mean, that lies between two contrary vices: one of excess and one of deficiency.

This mean is not a mathematical average but is relative to the individual and the situation, determined by rational principle.

For instance:

- the virtue of courage is the mean between the deficiency of cowardice and the excess of foolhardiness. The courageous person does not act without fear, but rather assesses the situation rationally, feels the appropriate level of fear, and acts rightly despite it.

- Similarly, generosity is the intermediate disposition between the vice of stinginess (deficiency) and that of profligacy (excess).

Discerning this mean in any given context requires the intellectual virtue of practical wisdom, or phronesis, which enables the moral agent to perceive what is ethically required in a particular situation.

Ultimately, virtue ethics reorients the fundamental questions of moral philosophy. Instead of asking, “What is the right action to perform?” as a deontologist or utilitarian might, the virtue ethicist asks, “What kind of person should I be?” and “What constitutes a flourishing life?” The primary focus shifts from the evaluation of discrete acts in isolation to an assessment of the long-term character of the moral agent.

An act of charity, for example, is judged less on the basis of a duty to give (deontology) or the positive outcomes it produces (utilitarianism), and more on whether it originates from a genuinely benevolent and compassionate character.

From this perspective, morality is an ongoing project of character development, cultivated through education, reflection, and consistent practice until virtuous conduct becomes second nature.

The Relevance of Virtue Ethics in the Digital World

While ancient in origin, virtue ethics offers a powerful lens for navigating the modern challenges of the digital age.

Digital environments are dynamic and complex. The consequences of an action, such as a social media post, are highly unpredictable—it could receive three likes or go viral, causing unforeseen harm or good. This inherent unpredictability poses a significant problem for consequence-based ethics like utilitarianism.

Virtue ethics offers a more robust guide. It suggests that in such environments, cultivating virtues of character and exercising prudential judgment is a more reliable approach than attempting to predict all possible outcomes. A person with virtues like conscientiousness, civility, and compassion is more likely to act responsibly online, regardless of the outcome. This makes virtue ethics a valuable preparatory framework, shaping agents to act well in novel situations.

Virtue ethics is inherently sensitive to context and particularity, unlike the rigid, universal rules of deontology. This flexibility is crucial in the digital domain, where relations of power and inequality (e.g., between platforms and users, or governments and citizens) are often more salient than in idealized ethical scenarios.

This adaptability helps overcome the weaknesses of deontological ethics, especially when rules and duties conflict.

For example:

- Conflict: The duty to respect user privacy can conflict with the duty to ensure transparency (e.g., for content moderation).

- Deontological Impasse: A rigid, rule-based system struggles to resolve this.

- Virtue Ethics Approach: A virtuous agent would use practical wisdom (phronesis) to find a balanced and just solution that appropriately weighs the competing values in that specific context.

Criticisms and Challenges of Virtue Ethics

Despite its intuitive appeal and focus on the holistic development of the moral agent, virtue ethics confronts several significant philosophical and practical challenges. A primary objection is the application problem, which concerns the theory’s perceived lack of clear, prescriptive guidance for action. While theories like deontology and utilitarianism provide explicit principles—such as the Categorical Imperative or the Principle of Utility—to resolve moral dilemmas, virtue ethics offers the more ambiguous advice to “act as a virtuous person would.” In complex ethical situations where virtues may conflict (e.g., when honesty clashes with compassion), this guidance can be insufficient for determining a concrete course of action, leaving the agent without a clear decision-making procedure.

Furthermore, the theory is sometimes criticized for promoting an unrealistic or utopian ideal of human character. The concept of the perfectly virtuous agent, or phronimos (the person of practical wisdom), can seem an unattainable standard for ordinary individuals navigating the complexities and moral imperfections of everyday life. This critique is often linked to the charge that virtue ethics may harbor a conservative bias. Because virtues are typically identified and cultivated within the traditions and social norms of a specific community, the theory risks endorsing the status quo and discouraging moral progress or criticism of established conventions. It may struggle to account for the “moral rebel” who challenges societal norms in the name of a higher, yet-to-be-recognized moral truth.

Another significant challenge arises from the problem of moral relativism. If the content of virtues is culturally determined, then what is considered a virtue in one society (e.g., martial honor) may be viewed as a vice in another. This variability makes it difficult to establish universal ethical standards or to engage in cross-cultural moral critique. Without a transcultural foundation for what constitutes human flourishing (eudaimonia), virtue ethics may struggle to condemn practices that are considered morally abhorrent from an external perspective but are nonetheless endorsed by the traditions of a particular culture.

From the field of empirical psychology comes the situationist critique, which challenges the fundamental premise of virtue ethics: the existence of stable, robust character traits. Influential studies in social psychology have suggested that external situational factors (such as authority pressure or group dynamics) are often far more predictive of an individual’s behavior than any presumed internal virtues like honesty or compassion. This research implies that character traits may not be the consistent, cross-situational dispositions that virtue ethics requires them to be, thus undermining the theory’s empirical foundations by questioning whether ‘virtues’ as such truly exist as reliable determinants of action.

Finally, virtue ethics faces difficulties when addressing issues of collective and systemic morality. The theory’s focus is inherently agent-centered, concentrating on the character and actions of the individual. Consequently, it is less equipped to analyze and provide solutions for large-scale ethical problems that are not reducible to the sum of individual actions. Issues such as systemic injustice, institutional bias, corporate responsibility, or global challenges like climate change require a framework that can account for collective agency, structural dynamics, and the ethics of policies and institutions, an area where the individualistic focus of traditional virtue ethics proves to be a significant limitation.

Case Study - Disinformation Online

The proliferation of disinformation in the digital sphere presents a formidable challenge to traditional ethical frameworks, forcing a re-evaluation of their applicability in a technologically mediated world. The core of the dilemma can be understood through the lens of Karl Popper’s paradox of tolerance. As articulated in The Open Society and Its Enemies, Popper argued that a society committed to unlimited tolerance will ultimately see its tolerant nature subverted by the intolerant. This creates a foundational tension: to preserve the conditions for an open and free society, it may become necessary to constrain certain freedoms, such as expression, when they are weaponised to undermine the autonomy and safety of others. This balancing act is particularly acute in the context of online platforms, where the line between protecting open discourse and preventing societal harm is increasingly difficult to draw.

The unique architecture of the modern internet exacerbates this ethical challenge. Unlike historical forms of propaganda, online disinformation operates at an unprecedented scale and velocity, capable of transforming localised falsehoods into global threats within hours. This dynamic is intensified by algorithmic amplification, as platform business models are often predicated on maximising user engagement, a metric that frequently favours sensationalist, emotionally charged, and factually incorrect content. Compounded by the prevalence of anonymity and the erosion of traditional journalistic gatekeepers, the digital ecosystem creates a fertile ground for the spread of harmful narratives without accountability, fundamentally altering the nature of the problem that ethical systems must now address.

Applying a deontological framework to this issue offers a compelling, though complex, solution. From this perspective, the principal moral duty is the respect for the autonomy of persons. Disinformation directly violates this duty by intentionally deceiving individuals, thereby corrupting their capacity for rational deliberation and preventing them from making informed choices about their lives and their societies.

Ethical Framework Application & Challenges Deontology Provides an acceptable solution. The core value to preserve is respect for the autonomy of persons. Disinformation undermines autonomy by preventing people from making informed decisions. Therefore, rules limiting disinformation can be justified to protect this fundamental value. However, this raises questions about who defines “disinformation” and what the rules should be, especially given the divergence of values in our digital future. Utilitarianism Faces practical difficulties. A utilitarian approach would require calculating the total pain caused by online conspiracies versus the pleasure/utility of free expression. This is nearly impossible due to the difficulty in quantifying the scale, duration, and intensity of the psychological and social harm fostered by disinformation. Virtue Ethics Has foundational problems here. This framework is based on the notion of human flourishing (eudaimonia) within a particular way of life. The challenge is that there is no single, agreed-upon vision of what a “flourishing” life looks like in a pluralistic, digitally mediated global society. Without this shared conception of the good life, it is difficult to define which virtues should guide our actions regarding disinformation. A deontologist could therefore justify the implementation of rules or policies that restrict disinformation, arguing that such measures are necessary to protect the fundamental conditions for autonomous agency. However, this approach immediately confronts the critical challenge of authority and definition: who possesses the legitimate authority to define “disinformation,” and what principles should guide the creation of rules to govern it without creating an apparatus for censorship that could itself be used to undermine autonomy?

A utilitarian analysis, by contrast, quickly runs into severe practical difficulties. This framework mandates that the morally correct action is the one that maximises overall happiness or well-being. To address online disinformation, a utilitarian would need to conduct a calculus, weighing the cumulative harms caused by its spread against the utility derived from an environment of unfettered free expression. This calculation is arguably impossible to perform with any degree of accuracy. The harms—including the erosion of social trust, the promotion of public health crises, political polarisation, and widespread psychological distress—are diffuse, long-term, and profoundly difficult to quantify. Similarly, quantifying the societal utility of protecting all forms of speech, including the false and malicious, is an intractable problem, rendering the utilitarian framework more of a theoretical diagnostic tool than a practical guide for policy.

Finally, virtue ethics encounters foundational problems when applied to the systemic issue of online disinformation. The primary obstacle is the absence of a singular, shared conception of a “flourishing life” within the pluralistic and fragmented context of a global, digitally-mediated society. Without a consensus on the telos, or ultimate purpose, of our digital communities, it becomes exceedingly difficult to define the specific virtues—such as intellectual humility, civic responsibility, or digital literacy—that ought to be cultivated. Furthermore, the agent-centered focus of virtue ethics is ill-suited to address a problem that is deeply structural, driven as much by algorithmic design and platform economics as by the moral failings of individual users.

Applying Ancient Virtues to Modern Dilemmas

A central challenge in contemporary applied ethics is the translation of classical ethical frameworks into the novel contexts of the digital world. Virtue ethics, with its origins in the ancient Greek city-state, requires significant adaptation to remain relevant.

The Aristotelian conception of human flourishing, or eudaimonia, was deeply embedded in the social and political life of the 5th-century BC Athenian polis, informing the very definition of virtues such as courage, justice, and magnanimity. The task for modern ethicists is to re-imagine what eudaimonia might constitute in today’s digitally-mediated, globalized, and pluralistic societies, a process that demands more than simple translation and instead calls for creative and critical re-evaluation.

Phronesis

The key to this adaptation lies in the intellectual virtue of phronesis, or practical wisdom. Aristotle considered phronesis to be the master virtue that enables an individual to navigate new and complex moral landscapes. It is the capacity to perceive the ethically salient features of a situation, to deliberate correctly about the best course of action, and to effectively integrate and apply other virtues. When confronted with an unprecedented ethical dilemma, a person exercising phronesis can engage in two distinct but related cognitive processes.

- The first is extension, whereby existing moral knowledge is applied to a new case through the use of analogy, drawing parallels between the unfamiliar and the familiar.

- The second, more demanding process is invention, which becomes necessary when a situation is so novel that existing analogies prove insufficient, requiring the creation of entirely new moral responses, norms, and understandings.

Case Study: Internet Addiction

The contemporary problem of internet addiction serves as an illustrative case for the application of phronesis. An initial attempt to understand this harm naturally proceeds by extension, drawing an analogy to a more familiar vice like drug addiction. This comparison is useful, as it allows us to import a known moral vocabulary, suggesting that the virtues of moderation and self-restraint are the appropriate responses. However, the analogy is imperfect and ultimately breaks down. Unlike illicit substances, the internet is an essential tool for social, economic, and political participation in modern life, meaning it cannot simply be proscribed or avoided.

This crucial difference highlights the limits of analogical reasoning and necessitates moral invention. The challenge of internet addiction is compounded by novel factors such as machine agency, where AI assistants and sophisticated algorithms are often explicitly designed to maximise engagement and foster compulsive behaviour. These systems introduce a new dimension to the ethical problem that has no historical precedent. Consequently, phronesis is required not merely to apply old virtues, but to invent new social norms, ethical design principles for technology, and potentially novel regulatory frameworks to cultivate a digital environment that is conducive to, rather than corrosive of, human flourishing.

Re-evaluating Virtue Ethics in the Context of Artificial Intelligence

The integration of advanced autonomous systems into human society necessitates a critical reassessment of classical ethical frameworks, particularly virtue ethics. A central challenge lies in determining the applicability of Aristotelian concepts, traditionally focused on human character and flourishing, to non-human, engineered entities.

The Status of Artificial Agents: Virtue and Moral Status

The question of whether a machine or robot can possess genuine virtues in the classical sense hinges on the prerequisites for moral action. A moral agent’s actions must be intentional, deliberate, and spring from a stable, cultivated character (hexis), where the agent is rightly disposed to act for the sake of the noble (to kalon). While an algorithm can be programmed to be “agreeable” or “efficient,” such behaviors are strictly instrumental and lack the crucial component of acting for the right reasons—a capacity rooted in practical wisdom (phronesis) and emotional disposition. Consequently, any ascription of virtues like “helpfulness” to a machine is purely metaphorical or, at best, a minimalistic, functional attribution, devoid of the deep ethical significance associated with human moral excellence.

Furthermore, the designation of machines as moral patients—beings capable of being wronged—is similarly contested under a virtue ethics lens. The concept of a moral patient is closely tied to the potential for harm that compromises an agent’s ability to achieve human flourishing (eudaimonia). Since robots, as artifacts, lack consciousness, sentience, and the capacity for eudaimonia, the arguments against them being true moral patients are persuasive. While practical and legal considerations may necessitate affording them certain protections, this recognition differs fundamentally from the inherent moral status attributed to beings capable of subjective experience and ultimate fulfillment.

The Need for Moral Courage and Humility

Contemporary philosophers, such as Shannon Vallor, emphasize the peril inherent in a static ethical approach that refuses to acknowledge the emerging reality of artificial agency. As algorithmic systems become increasingly autonomous and consequential, a simple dismissal based on traditional human-centric categories becomes ethically irresponsible. Addressing this requires a dynamic application of virtue ethics, demanding that human moral agents exercise specific intellectual and moral virtues.

This challenge necessitates a creative and rigorous exercise of phronesis to fundamentally re-examine the norms governing our social and political communities in light of technological advancement. Integral to this process are moral courage and intellectual humility. Courage is required to critically confront and admit the limitations and shortcomings of established frameworks—for instance, questioning whether the rigid person/thing dichotomy accurately reflects the moral complexity of advanced AI. Concurrently, humility is vital for navigating the ambiguous moral territory opened up by technology, facilitating an open-minded exploration of possibilities—such as the complex and ongoing public and academic discourse surrounding the notion of “robot rights”—without succumbing to defensive dogmatism.

Cultivating Moral Imagination as the Essential Future Virtue

Ultimately, the most critical virtue for human agents engaging with an AI-integrated future is moral imagination. The strength of virtue ethics in the domain of digital ethics is not that it provides a fixed set of answers or deontological rules, but rather that its teleological structure demands an active process of conceiving novel configurations of living well (euthenia) in a world co-inhabited by intelligent non-human agents. It offers a framework for inquiry rather than a rulebook.

This path, however, is inherently risky. Operating without the explicit, fixed guardrails of a rule-based system (like deontology) means that an unconstrained moral imagination risks descending into moral chaos or serving to justify harmful or self-serving ideologies. The principal challenge, therefore, lies in navigating this profound uncertainty—the space between established tradition and technological novelty—through a rigorous commitment to constant critical reflection and inclusive, robust public deliberation, thereby counteracting the tendency toward moral relativism.

Reference

![[3 - Ethics, Technology And Engineering 66-101 [79-122].pdf]]