Decision theory, as introduced by Jay R. Galbraith (1973, 1977), provides a framework for understanding how organizations process information and make decisions under conditions of uncertainty. It emphasizes that organizations should be viewed as open systems, meaning that their success is not solely determined by their internal production processes but rather by their ability to adapt to the external environment. From this perspective, an organization must be analyzed within the context of its market environment, rather than as an isolated system of production. The company’s ability to sell its product is shaped by external factors such as competition, customer demand, regulatory constraints, and technological advancements. This shift in focus underscores the need for organizations to develop dynamic capabilities that enable them to continuously adapt to environmental changes.

The Uncertainty Problem

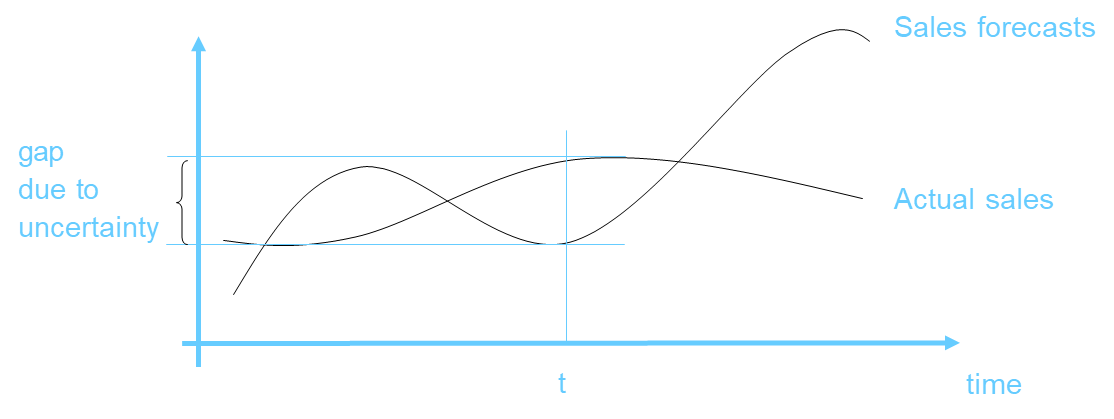

A fundamental concept in decision theory is uncertainty, which serves as the key variable describing the external environment in which an organization operates.

Definition

Uncertainty refers to the extent to which an organization can predict future market conditions, particularly customer demand, supply chain stability, and competitive forces.

Organizations operating in highly unpredictable environments must invest in more sophisticated information processing systems to enhance decision-making and maintain a competitive edge.

Several factors contribute to the level of uncertainty faced by an organization, including:

- Market Dynamism: The frequency and magnitude of changes in customer preferences, competitor strategies, and technological innovations. Rapidly evolving markets create greater uncertainty.

- Number of Suppliers in the Market: A higher number of suppliers can introduce complexity in procurement and supply chain management, while a lack of supplier diversity can increase risk.

- Variety and Variability of Market Requirements: The extent to which customer preferences differ and how frequently they change over time. Greater variability increases the need for flexible and responsive business strategies.

- Degree of Innovation: Industries characterized by frequent technological advancements experience higher uncertainty, requiring organizations to continually adapt to remain competitive.

Galbraith’s decision theory suggests that organizations must develop information-processing mechanisms that match the level of uncertainty in their environment. This can be achieved through structural adjustments, such as decentralization of decision-making, enhanced communication channels, and the adoption of advanced IT systems to facilitate real-time data analysis. By aligning their decision-making processes with environmental complexity, organizations can improve their adaptability, strategic responsiveness, and overall effectiveness.

Bounded Rationality

Bounded rationality is a fundamental concept in organizational theory that addresses the cognitive limitations of decision-makers when processing information and making choices. Originally introduced by Herbert Simon, bounded rationality highlights the fact that managers, like all humans, have limited cognitive capacity, which affects their ability to evaluate all possible alternatives in complex decision-making scenarios.

Since organizations operate in dynamic environments, managers frequently encounter situations where they must respond to change and uncertainty. However, due to bounded rationality, they cannot process infinite amounts of data or foresee all potential consequences of their decisions. As a result, organizations develop cooperative structures to compensate for individual cognitive limitations.

The consequences of bounded rationality include:

- Need for Cooperation: Since no single individual can process all necessary information, cooperation becomes essential to share and distribute knowledge effectively.

- Specialization: Organizations assign specific roles and tasks to individuals, allowing them to focus on particular domains, which increases efficiency but also creates information interdependencies between units.

- Coordination of Interdependencies: As specialization leads to fragmented knowledge, organizations must develop mechanisms to coordinate and integrate different information streams to function effectively.

- Organizational Purpose: The need to manage these interdependencies is one of the primary reasons why organizations exist. Without structured coordination, individual decision-makers would struggle to handle complex, large-scale tasks.

- Role of IT as a Coordination Technology: Since IT facilitates information processing, communication, and decision support, it serves as a key coordination tool in modern organizations, helping overcome the limitations of bounded rationality.

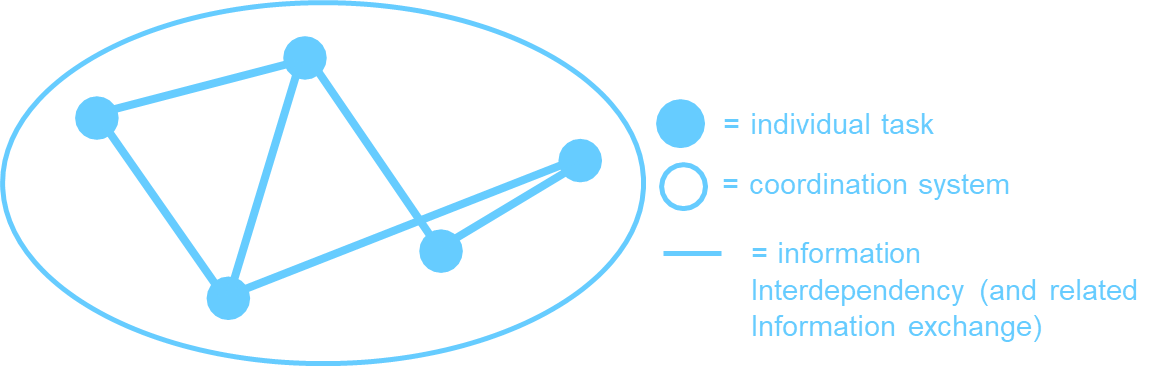

Information Interdependencies

In an organizational setting, the effective management of information interdependencies is essential for ensuring smooth coordination between different functions. This necessity arises from the concept of bounded rationality. As a result, tasks must be divided among different individuals and departments, creating a network of interdependent activities that rely on the exchange of critical information.

An organization consists of multiple specialized functions, each responsible for specific tasks. However, these functions do not operate in isolation; they must coordinate and share information to achieve common goals.

Without structured mechanisms for information exchange, these interdependencies can lead to inefficiencies, delays, and miscommunication, ultimately hindering organizational performance.

The challenge in managing information interdependencies stems from the fact that individuals working in different departments often focus on their immediate responsibilities, sometimes without a clear understanding of how their work impacts other functions.

Example

Consider a scenario where the engineering department is developing a new product. While engineers may be primarily concerned with technical feasibility, the sales and marketing teams need timely access to product details to plan promotional campaigns and customer outreach strategies. If engineers fail to communicate key specifications to marketing in a timely manner, the company risks launching an ineffective sales campaign, leading to lost opportunities and revenue.

To address this challenge, organizations must implement structured coordination mechanisms that facilitate the seamless flow of information between interdependent functions. These mechanisms can take various forms, including formal communication channels, cross-functional teams, and digital information systems. For example, many companies utilize Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems, which centralize data and allow different departments to access relevant information in real time. Such systems reduce inefficiencies caused by fragmented communication and ensure that all organizational units operate based on the same up-to-date information.

Beyond technological solutions, organizational culture and training also play a crucial role in managing information interdependencies. Employees must be trained to recognize the importance of information exchange and collaboration across departments. In cases where departmental silos exist, structured initiatives such as interdepartmental workshops, joint meetings, and cross-functional project teams can help bridge the gap between different functions. These initiatives encourage employees to understand the broader organizational objectives and the significance of their contributions to collective success.

Another key aspect of managing information interdependencies is the role of hierarchical structures and managerial oversight. While decentralized decision-making can promote flexibility, certain types of information require centralized coordination to ensure consistency and strategic alignment. For example, pricing strategies often require input from multiple departments, including marketing, finance, and operations. In such cases, senior management must oversee the decision-making process to ensure that all relevant information is considered before finalizing a strategy.

Warning

However, it is important to recognize that coordination efforts must be balanced to avoid unnecessary bureaucracy and delays. Excessive formalization of information exchange can create bottlenecks, slowing down decision-making processes. Organizations must strike a balance between structured coordination mechanisms and flexibility, allowing employees to adapt dynamically to changing conditions while ensuring that critical information flows efficiently.

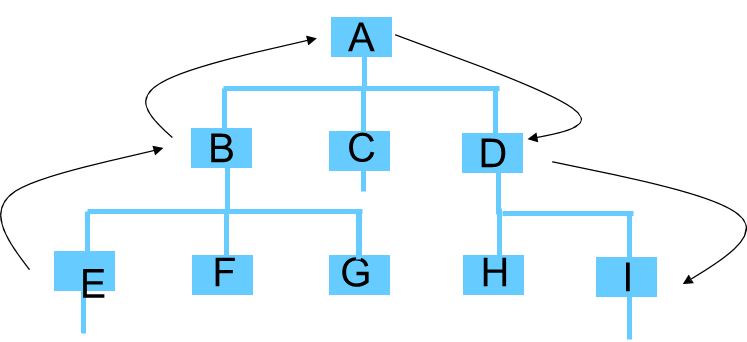

Hierarchical Coordination Systems

The hierarchical coordination system is a fundamental organizational structure that relies on command and control mechanisms to manage operations.

Command & Control Definition

It is a system in which decision-making authority is concentrated at the top, with responsibilities delegated down the chain of command.

This structure has traditionally been used in large corporations, government institutions, and military organizations due to its clear lines of authority and standardized procedures.

Within a hierarchical system, organizations typically adopt a functional approach to task division. This means that tasks are assigned to specialized departments such as marketing, sales, production, finance, and human resources. While this structure ensures expertise within each function, it also creates information interdependencies—a situation where one department’s work is reliant on timely and accurate input from another. Managing these interdependencies becomes a challenge, as the hierarchical nature of the organization enforces strict communication channels, typically following vertical and horizontal information flows.

Hierarchical structures primarily depend on vertical information systems, where information moves top-down (from executives to employees) or bottom-up (from employees to management). However, to handle increasing complexity and interdepartmental dependencies, organizations also rely on horizontal (or lateral) information systems, which facilitate direct communication between functions. The ultimate goal of these systems is to reduce uncertainty by ensuring that critical information reaches the right individuals at the right time.

Vertical Information Systems

Definition

A vertical information system is designed to facilitate the flow of information along hierarchical relationships within an organization. In this system, communication moves up and down the hierarchy, following the chain of command.

This structure is common in traditional, bureaucratic organizations where decision-making authority is centralized, and lower-level employees must seek approval from higher levels before taking action.

One of the key functions of vertical information systems is to address environmental uncertainty, which arises from unpredictable changes in the market, technology, regulations, or consumer preferences. Since uncertainty leads to exceptions—situations that deviate from standard procedures—the organization must develop mechanisms to handle them effectively.

The process works as follows:

- Environmental uncertainty generates exceptions (unexpected events or problems that require managerial intervention).

- Exceptions increase the need for planning and control, as predefined procedures may not be sufficient to address them.

- Planning and control create information processing demands, requiring managers to assess, analyze, and respond to exceptions effectively.

Since exceptions often require input from higher hierarchical levels, information flows vertically towards top management, who are responsible for making strategic decisions. However, this system has inherent limitations.

Limitations of Vertical Information Systems

While vertical information systems provide clear lines of authority and accountability, they also introduce several inefficiencies, particularly in dynamic environments:

- Slow decision-making: Because information must travel up the hierarchy for approval, responses to urgent issues may be delayed.

- Information bottlenecks: Senior managers may become overwhelmed with information, reducing their ability to make timely and informed decisions.

- Rigid structure: The strict flow of communication can hinder innovation and adaptability, as lower-level employees may hesitate to share insights without formal approval.

To overcome these limitations, many organizations supplement vertical systems with horizontal (lateral) information systems, which enable faster, more flexible decision-making.

Horizontal (Lateral) Information Systems

Unlike vertical systems, which emphasize top-down control, a horizontal (or lateral) information system facilitates direct communication between units at the same hierarchical level. This system is particularly useful in organizations that require frequent collaboration across different functions, such as project-based firms, technology companies, and organizations operating in highly dynamic industries.

The main characteristics of horizontal information systems are the following:

- Direct communication between departments: Instead of routing information through the hierarchy, employees and teams communicate directly with their counterparts in other units.

- Greater delegation of decision-making: Since managers do not need to approve every decision, employees have more autonomy to solve problems and take initiative.

- Flexibility and adaptability: Teams can respond quickly to market changes, customer needs, and emerging challenges without waiting for executive approval.

Organizations use various mechanisms to support lateral information exchanges and enhance cross-functional collaboration:

graph LR LR[Liaison<br>Roles] --> TF[Task<br>Force] --> Teams --> MS[Matrix<br>Structure]

- Liaison Roles: A designated liaison officer or coordinator facilitates communication between different departments. This person ensures that relevant information flows smoothly and that different teams are aligned.

- Task Force: Temporary cross-functional teams are formed to address specific problems or projects. These teams bring together individuals from different departments to collaborate intensively before disbanding once their objective is achieved.

- Teams: Permanent or semi-permanent cross-functional teams are established to work on ongoing projects or initiatives. These teams are responsible for integrating expertise from various functions to achieve common goals.

- Matrix Structures: A matrix organization assigns employees to multiple reporting lines (typically to both a functional manager and a project manager). This structure ensures that expertise from various departments is integrated into key projects while maintaining functional specialization.

Comparing Vertical and Horizontal Information Systems

Feature Vertical Information System Horizontal Information System Primary Communication Flow Top-down and bottom-up Lateral (across departments) Decision-Making Authority Centralized at higher levels Delegated across teams Response to Uncertainty Slow due to hierarchical approval Fast due to direct coordination Adaptability Less adaptable to rapid change Highly adaptable and flexible Efficiency in Complex Tasks Can lead to bottlenecks and delays Facilitates real-time problem-solving

Challenges in Hierarchical Communication

Despite its structured nature, a hierarchical coordination system presents significant limitations in handling complex and dynamic environments. The formal chain of command, designed to maintain order and accountability, often introduces inefficiencies in decision-making and communication.

Example

Consider a scenario in which an employee in production requires urgent data from finance to estimate the cost of manufacturing a new product. Instead of directly reaching out to a finance team member, the employee must follow protocol by reporting the request to their immediate supervisor. The supervisor, in turn, forwards the request up the hierarchy until it reaches someone with the necessary authority to communicate with finance. Once the finance department processes the request, the response follows the same hierarchical path back down. This rigid system slows down operations, especially when multiple approvals are needed.

Such bureaucratic delays become even more problematic when organizations operate in highly uncertain environments where rapid decision-making is critical. In industries characterized by frequent market fluctuations, technological advancements, and regulatory changes, the traditional hierarchy struggles to adapt quickly to emerging challenges.

Additionally, organizations face increased risks of information bottlenecks. Since communication is filtered through multiple layers of management, critical information can be distorted, delayed, or even lost before reaching the intended recipient. As a result, employees at operational levels may not receive timely updates, leading to inefficiencies, misaligned objectives, and reduced responsiveness.

Due to these inefficiencies, many organizations are exploring alternative coordination mechanisms to complement or even replace traditional hierarchical structures. Some of these include:

- Decentralized decision-making: Empowering lower-level managers and employees to make decisions within their areas of expertise reduces the need for excessive approval processes.

- Cross-functional teams: Creating project-based teams composed of individuals from multiple departments fosters direct communication and collaboration, minimizing reliance on vertical channels.

- Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems: These integrated information systems allow real-time data sharing across departments, streamlining interdepartmental coordination.

- Agile and Matrix Structures: Many modern organizations adopt agile frameworks or matrix structures, where employees report to multiple managers or teams, facilitating more flexible communication.

While hierarchical coordination remains a valuable system for maintaining structure and control, its limitations in managing complex and fast-changing environments make it necessary for organizations to integrate more flexible and adaptive coordination models. Finding the right balance between hierarchical stability and operational agility is key to maintaining efficiency and responsiveness in today’s competitive business landscape.

Environmental Uncertainty and Information Processing Capacity

In the dynamic landscape of modern markets, businesses must navigate the challenges posed by environmental uncertainty and the evolving demands of consumers. As markets mature, organizations shift their focus from generating initial demand to sustaining long-term consumer interest. This transition is particularly evident in industries where technological advancements and product life cycles dictate market behavior. Initially, when a new product enters the market, consumers exhibit enthusiasm, leading to strong sales. However, as the product becomes widespread, companies must confront a critical question: how can they persuade customers who already own an earlier version to invest in an updated model?

This challenge is especially prominent in manufacturing industries, where firms must balance product longevity with continued sales. A common approach to sustaining demand involves planned obsolescence, a strategy in which products are deliberately designed to have a finite lifespan, necessitating periodic replacements. While this method can drive sales, it is not without its drawbacks. Consumers, particularly those who invest in high-quality, durable goods, may resist purchasing new models if their existing products remain functional.

Example

For example, a consumer who has spent a significant amount on a premium washing machine may be reluctant to replace it unless a compelling reason justifies the expense. This creates a paradox for businesses: they must ensure their products are reliable and long-lasting while simultaneously encouraging repeat purchases.

The Strategic Response to Market Uncertainty

Organizations operating in competitive industries must continuously adapt their strategies to mitigate the effects of market volatility. The balance between cost efficiency and product quality plays a crucial role in shaping consumer behavior. High-quality products foster brand loyalty, but their extended durability may reduce the frequency of repeat purchases, impacting long-term revenue. To counteract this, firms employ marketing and innovation-driven approaches to stimulate demand. For instance, incremental technological improvements, aesthetic redesigns, and software-based enhancements can create incentives for consumers to upgrade without relying solely on physical deterioration.

Beyond consumer behavior, environmental uncertainty introduces another layer of complexity. Market fluctuations, regulatory changes, and shifting consumer preferences demand a robust information processing capacity within organizations. Traditional corporate structures, particularly those governed by vertical information systems, often struggle to respond effectively to rapid changes. In these systems, decision-making authority is concentrated at the higher levels of the hierarchy, requiring information to travel through multiple layers before actionable insights emerge. This hierarchical bottleneck can result in delayed responses, limiting an organization’s ability to capitalize on emerging opportunities or address challenges in real time.

The Need for Decentralized Decision-Making

To navigate uncertainty more effectively, organizations must consider delegating decision-making authority to lower levels of the hierarchy. This decentralization empowers employees to take initiative, respond swiftly to unforeseen circumstances, and contribute meaningfully to the company’s strategic direction. However, transitioning from a top-down control model to a distributed decision-making structure requires a fundamental shift in managerial philosophy. Leaders accustomed to centralized authority may find it challenging to entrust employees with autonomy. Nevertheless, fostering a culture of trust and responsibility is essential for businesses seeking to remain agile in volatile environments.

In contemporary workplaces, particularly those that attract younger professionals, there is an increasing expectation for employees to engage proactively rather than passively follow directives. Organizations that embrace this shift benefit from a more dynamic, innovation-driven workforce capable of adapting to challenges with minimal managerial oversight. The key to success lies in creating an organizational framework that balances structure with flexibility, ensuring that employees have clear responsibilities while retaining the freedom to make informed decisions.

The Role of Organizational Structures in Managing Uncertainty

Rigid hierarchical models can hinder an organization’s ability to process exceptions—situations that deviate from standard operational procedures. As environmental uncertainty increases, exceptions become more frequent, necessitating alternative coordination mechanisms. In response, modern enterprises are shifting toward horizontal (lateral) information systems, which facilitate direct collaboration across departments and reduce reliance on strict hierarchical approval processes.

One widely adopted approach is the matrix structure, which integrates elements of both vertical and horizontal coordination. In a matrix organization, employees report to both functional managers (who oversee expertise within specific domains) and project managers (who coordinate cross-functional teams). This dual-reporting structure enhances information flow and enables faster decision-making, making it particularly suited for industries characterized by high uncertainty and rapid technological advancement.

A practical example of an organization leveraging flexible structures is found in consulting firms, where employees often work across multiple projects simultaneously. Unlike traditional corporations, consulting firms prioritize agility and responsiveness, allowing teams to be reconfigured based on evolving client needs. While this approach offers significant advantages in terms of adaptability, it also introduces challenges related to coordination costs and the need for clear role definition. Ensuring that information exchange remains seamless within such dynamic environments is crucial for maintaining operational efficiency.

Case Studies in Adaptive Organizational Design

The importance of flexible structures extends beyond the corporate sector and into higher education institutions. A notable example is the Erasmus program, which facilitates student exchanges across European universities. Initially, the program encountered significant administrative hurdles due to the rigid, bureaucratic frameworks of academic institutions. Differences in credit allocation systems between universities created confusion, complicating the transfer process for students. Over time, efforts to standardize credit recognition across Europe have improved the program’s accessibility, highlighting the need for institutional adaptability in managing cross-border initiatives.

A more recent case of organizational adaptation can be seen in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitated a rapid transition to remote work and digital learning. Universities, traditionally reliant on face-to-face instruction, had to develop online learning infrastructures almost overnight. The urgency of the situation led to the formation of task forces, temporary teams assembled to address critical challenges. These task forces played a pivotal role in developing virtual classrooms, restructuring assessment methodologies, and ensuring academic continuity. Unlike permanent teams, which handle ongoing responsibilities, task forces are designed for short-term problem-solving, disbanding once their objectives are achieved.

In contrast, cross-functional teams serve a more enduring purpose. These teams bring together professionals from diverse backgrounds to collaborate on long-term projects, such as software development or product innovation. For example, a company developing a mobile application may establish a team comprising software engineers, user experience designers, marketing strategists, and customer support specialists. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, such teams enhance an organization’s ability to anticipate user needs and implement iterative improvements.

The Future of Information Processing in Organizations

As organizations continue to navigate an era of increasing complexity, the ability to process information efficiently and make timely decisions will become a critical determinant of success. Firms must invest in advanced information systems, leveraging data analytics, artificial intelligence, and cloud-based collaboration tools to enhance decision-making. The shift toward decentralized, team-based structures will likely accelerate, with companies prioritizing flexibility, innovation, and rapid adaptability over rigid hierarchical control.

Ultimately, businesses that strike the right balance between structure and agility will be best positioned to thrive in uncertain environments. By embracing horizontal coordination, empowering employees, and leveraging technology, organizations can enhance their capacity to process information effectively, ensuring sustained competitiveness in an ever-evolving global landscape.

Limitations of the Decision Theory and the Shift Towards Transaction Cost Economics

The Decision School, which primarily focuses on rational decision-making within organizations, presents certain limitations that necessitate alternative approaches. As businesses operate in increasingly complex environments, it becomes evident that traditional models of decision-making do not fully capture the intricacies of organizational behavior. Two major theoretical perspectives, Transaction Cost Economics and Agency Theory, offer alternative viewpoints that address these limitations and introduce additional layers of complexity to our understanding of organizational coordination.

One of the fundamental constraints of the Decision School is its assumption that environmental uncertainty is the only relevant form of uncertainty that organizations face. Environmental uncertainty refers to unpredictable external factors such as market fluctuations, economic trends, and competitive dynamics. While these are crucial elements, they do not constitute the entirety of uncertainty within an organization. A company’s strategic planning does not end with predicting market trends; rather, it must also address internal complexities that arise from human behavior, decision-making structures, and organizational coordination mechanisms.

A critical aspect often overlooked by the Decision School is that hierarchy and control are not the only methods of coordination within an organization. Traditionally, firms have operated under a command-and-control structure, where managers issue directives, and employees are expected to comply. However, modern management approaches emphasize a decentralized, objective-driven model, where employees are given goals to achieve rather than being micromanaged on their daily tasks. This shift is particularly evident in contemporary workplaces, where flexible working arrangements and performance-based assessments are replacing rigid supervision. Employees are increasingly expected to act as independent decision-makers rather than passive executors of managerial directives.

Transaction Cost Economics and Behavioral Uncertainty

Transaction Cost Economics (TCE) addresses these limitations by emphasizing behavioral uncertainty and opportunistic behavior—where individuals act based on self-interest, which may not always align with organizational objectives. TCE argues that firms must design efficient governance structures to minimize inefficiencies caused by incomplete control.

A major insight from TCE is that market-based coordination can be more effective than rigid hierarchies. Instead of micromanaging employees, organizations can use performance incentives, contractual agreements, and goal-oriented management to guide behavior. This reduces monitoring costs while ensuring alignment with company objectives. However, excessive autonomy without oversight can lead to misalignment. Organizations must strike a balance between flexibility and accountability, ensuring employees have both the freedom to make decisions and the incentives to align their choices with strategic goals.

The shift from hierarchical control to decentralized decision-making reflects broader changes in organizational management. Modern businesses rely on real-time data, cross-functional collaboration, and adaptive strategies rather than rigid bureaucratic structures. Leadership roles also evolve, with managers acting as mentors and facilitators rather than enforcers of compliance.

Conclusion

The Decision School, while foundational in management theory, falls short in addressing the complexities of modern organizations. Its reliance on hierarchical control and its narrow focus on environmental uncertainty overlook critical aspects of human behavior and organizational dynamics. Transaction Cost Economics provides a more nuanced perspective by introducing behavioral uncertainty and emphasizing market-based coordination mechanisms.

As businesses continue to evolve, the principles of TCE suggest that organizations should move away from rigid structures and embrace flexible, objective-driven management approaches. This shift not only enhances efficiency but also fosters a work environment where employees are empowered to make strategic decisions that align with both personal and organizational goals. By understanding and addressing the limitations of traditional decision-making models, companies can develop more effective coordination strategies that ensure long-term success in an increasingly complex business landscape.