Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems are comprehensive software platforms designed to manage and integrate core business processes within an organization. ERP systems provide a centralized platform that facilitates resource planning by connecting various departments, ensuring efficient data flow, and promoting real-time decision-making.

Unlike standalone applications that serve specific departmental needs, ERP systems offer a unified solution that encompasses various functions such as finance, supply chain management, human resources, customer relationship management (CRM), and manufacturing.

A key aspect of ERP implementation is the realization that it is not merely a technical endeavor but a transformative organizational process. Companies must undergo significant structural changes to align their operations with the system’s integrated nature. This often requires redefining business processes, training employees, and adapting to new workflows. Without this organizational readiness, the ERP implementation is likely to fail, regardless of how advanced the software is.

ERP Systems and Company Maturity

ERP systems are not one-size-fits-all solutions. The type of ERP a company needs depends significantly on its size, operational complexity, and organizational maturity. Smaller companies may initially operate without a formal IT system, managing administrative tasks using basic accounting software. As they grow, they may integrate specific applications for operational management. However, as the business scales further, the need for a unified ERP becomes apparent.

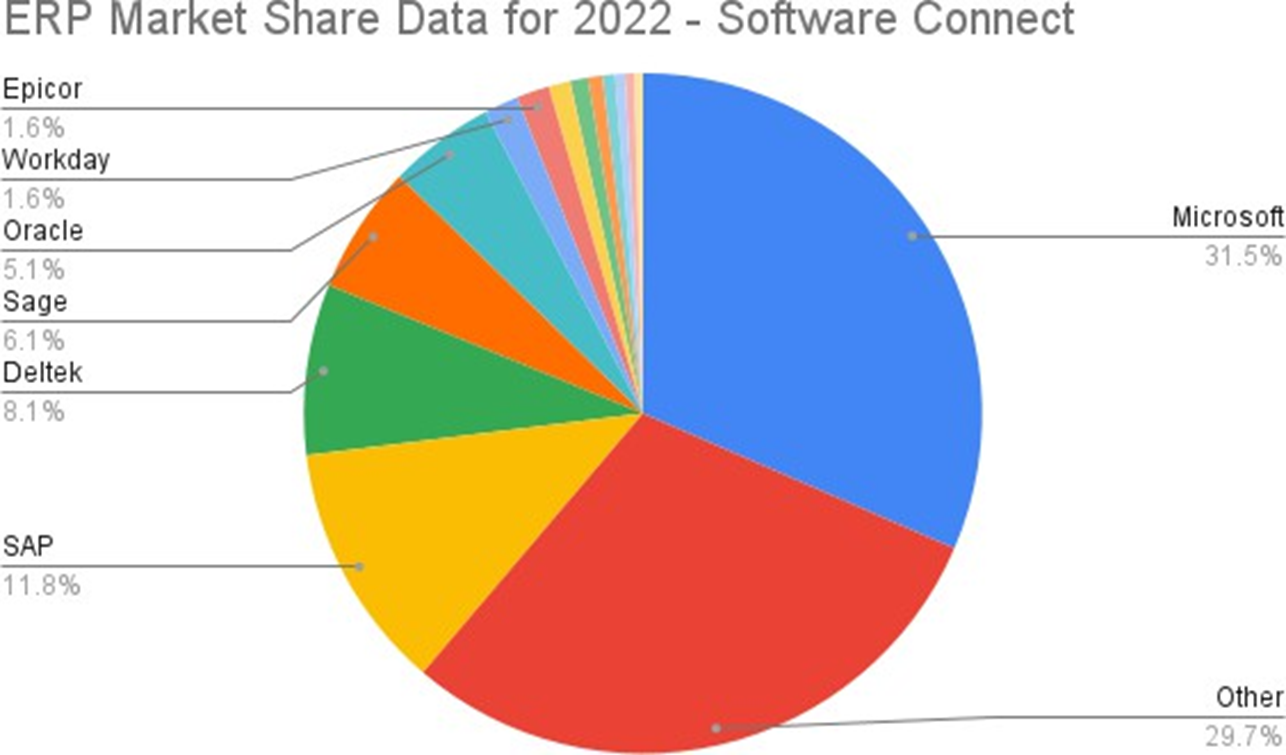

For large enterprises, comprehensive ERP platforms like SAP or Oracle offer sophisticated functionalities that support complex global operations. These systems enforce strict process standardization, ensuring consistency across all business units.

A key determinant in choosing an ERP system is the company’s decision-making structure and the degree of process standardization. Highly mature organizations with well-defined processes benefit from the automation and control that an ERP provides. In contrast, companies with fragmented or informal processes may struggle with the constraints of a robust ERP system. For them, a more adaptable solution that allows process flexibility may be more appropriate.

Standardization and Flexibility in ERP Implementation

ERP systems typically operate on standardized workflows that guide users through predefined steps, ensuring procedural compliance. In platforms like SAP, once a process step is completed, it becomes irreversible. This level of control is essential for large enterprises with complex operations requiring strict oversight.

Conversely, smaller companies may require greater flexibility. Local or mid-sized ERPs often provide customizable workflows, allowing users to modify or revert actions. This adaptability is particularly beneficial for businesses that rely on agility and continuous adjustments in their operations.

Moreover, ERP modules can be selectively implemented based on a company’s immediate needs. For example, an organization may choose to initially deploy modules for finance and supply chain management while gradually expanding to include CRM, manufacturing, or business analytics. This phased approach helps companies manage the complexities of ERP implementation without overwhelming their operations.

Parameterization and Customization in ERP

One of the primary advantages of ERP systems is their parameterization capability. Through a visual GUI, users can configure the ERP by adjusting predefined parameters rather than engaging in complex programming. These parameters cover a wide range of operational aspects, including product catalogs, warehouse configurations, production processes, and financial workflows. By simply setting values within these interfaces, companies can customize the ERP to reflect their specific business processes.

The process of ERP implementation has become increasingly efficient over time. Historically, implementing large-scale ERP solutions such as SAP could take over a year. However, improvements in consulting methodologies, advancements in software design, and the introduction of lightweight ERP versions have significantly reduced implementation times. Today, companies can deploy simplified ERP solutions within as little as three months, depending on their business size and operational complexity.

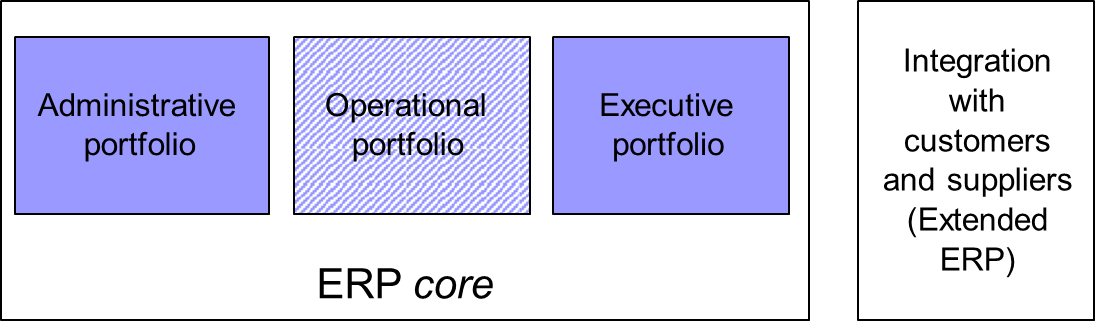

Core ERP and Extended ERP

ERP systems are generally composed of core modules and extended modules. Core ERP modules encompass essential administrative, operational, and executive functionalities, which form the foundation of the system. These include finance management, human resources, procurement, inventory management, and production planning. They are designed to ensure seamless internal operations by providing a unified platform for data management and process automation.

On the other hand, extended ERP modules offer additional functionalities that extend beyond internal operations. These modules typically focus on inter-organizational integration, enhancing collaboration with external stakeholders such as suppliers, customers, and business partners. Some of the most common extended ERP modules include:

- Supply Chain Management (SCM): Facilitates end-to-end supply chain visibility and management, from procurement to production and distribution.

- E-Procurement: Streamlines purchasing processes by enabling digital communication with suppliers.

- E-Commerce and E-Business: Supports online sales and service channels, integrating customer interactions with back-end systems.

- Workforce Management: Assists in labor management, shift planning, and employee performance monitoring.

| Core ERP Modules | Extended ERP Modules |

|---|---|

| Administrative porfolio | Customer Relationship Management (CRM) |

| Operational portfolio (industry department, vertical solutions) | Supply Chain Management (SCM) |

| Executive porfolio | E-Procurement and Market Place |

Vertical Solutions

Vertical solutions within ERP systems are industry-specific modules designed to address the unique operational and regulatory requirements of particular sectors. Recognizing that industries such as healthcare, finance, retail, and manufacturing each have distinct needs, ERP vendors offer customized solutions with specialized features.

Example

For instance, SAP provides a broad range of vertical solutions covering public services, consumer industries, financial services, and manufacturing. Within these verticals, further subcategories exist. The financial services sector, for example, includes dedicated modules for insurance, asset management, and banking operations.

Industry leadership in ERP solutions varies based on sector-specific expertise. While SAP is often a dominant player in large-scale enterprises, it may not be the market leader in all industries.

For example, Microsoft Dynamics is widely recognized as the global leader in the textile and apparel industry due to its specialized features that cater to supply chain management and retail operations.

When choosing an ERP system, companies must evaluate the software’s alignment with their industry needs, considering factors such as:

- Industry-specific functionality: Does the ERP offer modules designed for the specific operational challenges of the industry?

- Regulatory compliance: Can the ERP ensure compliance with industry standards and legal regulations?

- Scalability and Flexibility: Will the ERP accommodate business growth and adapt to changing operational requirements?

- Integration Capabilities: How well does the ERP integrate with other systems, including third-party applications and legacy software?

Selecting the right ERP system involves understanding both the vertical specialization offered by the vendor and the organization’s internal maturity level. Companies with well-defined, standardized processes are more likely to benefit from robust ERP solutions like SAP. In contrast, smaller or mid-sized enterprises may find value in more flexible solutions with fewer constraints.

ERP Paradigm: Key Pillars

The concept of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) is grounded in a specific set of paradigms that define its functionality and purpose within an organization. At the core of every ERP system, there are three fundamental pillars: information integration, extension and modularity, and process prescriptiveness. These pillars form the foundation upon which modern ERP systems are built, allowing them to streamline complex business operations and facilitate seamless data flow across various organizational functions.

Information Integration

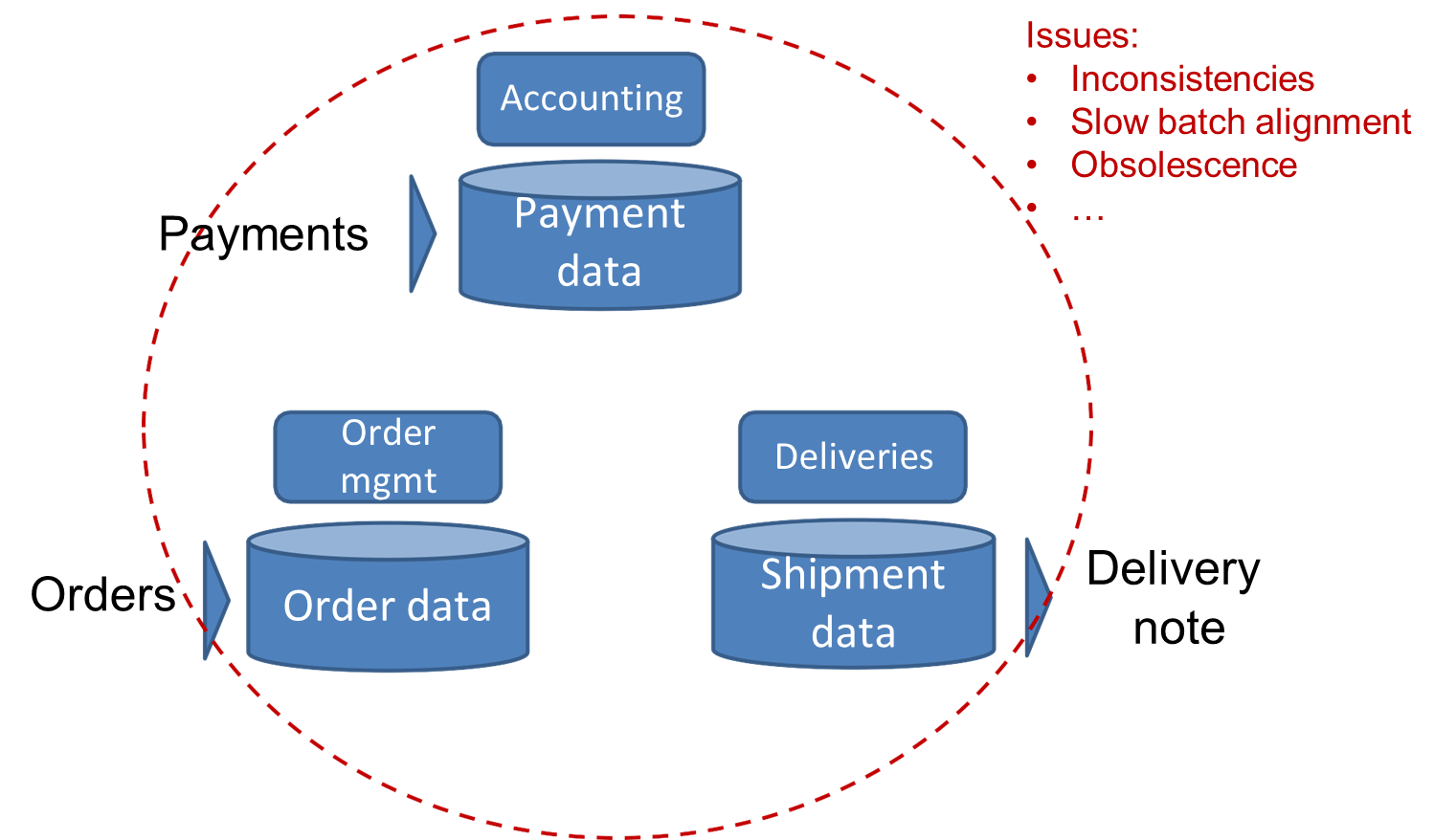

Information integration is a fundamental principle of ERP systems, aiming to unify and streamline the flow of data across an organization. The concept rests on the idea that all information within an enterprise should be consolidated into a single, unified system to ensure consistency and accuracy. When discussing information integration, it’s crucial to understand that it applies not only within one department but across all business functions.

For example, the data entered by the upstream activities—such as sales, inventory management, or procurement—should seamlessly feed into the downstream activities, including production, financial reporting, and customer service.

This integration is vital because it minimizes the risk of errors and discrepancies that often arise when different departments operate on separate, disconnected systems. In an ERP system, ensuring that data is “one” means that all modules, whether related to finance, production, or human resources, share the same database, which maintains the integrity and consistency of the information throughout the organization. This unified data system allows for better decision-making, as it ensures that every department is working with the same set of accurate and up-to-date information. Without integration, processes cannot be aligned, and decision-making becomes fragmented, making it harder to achieve operational efficiency.

From a technical perspective, the integration process involves establishing a centralized database that serves as the foundation for all the modules within the ERP system. Each module, whether related to procurement, manufacturing, or customer service, accesses and updates the central database, ensuring that the entire organization operates on the most current and accurate data. This integration also supports real-time updates, so when one department updates information, such as an inventory count or customer order, other departments are immediately informed and can adjust their operations accordingly.

Extension and Modularity

The second pillar of ERP systems is extension and modularity, which refers to the ability of an ERP solution to expand and adapt to the evolving needs of a company. ERPs are designed to be flexible, allowing organizations to scale their systems as they grow and diversify their business functions.

Definition

Extension means that the ERP system can encompass all business needs, offering solutions for different operational areas, from finance and human resources to production and supply chain management.

ERP systems are typically functionally complete, offering a wide range of modules that cater to different aspects of business operations. These modules are designed to cover a comprehensive array of business needs, from managing supply chains to handling human resource tasks.

The modular nature of these systems allows companies to choose the best modules for their needs, providing a level of flexibility and control. In some cases, organizations may opt for a “One Stop Shopping” approach, selecting all their modules from a single ERP vendor. This simplifies integration and ensures consistency across the system. Alternatively, businesses might prefer a “Best of Breed” strategy, where they select the best module from different vendors for each business function, ensuring that they get the most advanced or specialized capabilities for each area.

Example

In practice, SAP’s ERP system offers a wide range of modules, each designed to support specific business functions. Some of the most common modules include Sales and Distribution (SD), Materials Management (MM), Production Planning (PP), Quality Management (QM), and Project Management (PS). These modules can be implemented individually or as part of a broader, integrated ERP solution, depending on the company’s size, industry, and needs.

This modular approach provides significant advantages in terms of preparedness. It allows companies to implement the system in phases, ensuring that they are not overwhelmed by complexity. Additionally, modularity enables businesses to customize their ERP system to their specific needs, reducing the risk of over-complication and unnecessary features. As a result, companies can tailor their ERP system to match their operational requirements and capacity for change, without being forced to adopt functionalities they don’t yet need.

However, while this approach adds flexibility, it also comes with challenges. The company must be prepared to manage the rollout of additional modules effectively. This means assessing the organization’s readiness for each phase and ensuring that the team has the necessary resources and training to handle the new functionalities as they are introduced. Modularity ensures that an ERP system grows with the company, adapting to changes in the business environment and evolving operational needs.

Process Prescriptiveness

Despite the flexibility offered by modularity, ERP systems also introduce a level of process prescriptiveness that can be a limitation for some organizations. ERP vendors typically offer pre-configured, standardized processes that are based on best practices, designed to be efficient and effective across a wide range of industries, but they may not perfectly align with every company’s unique workflows or business model.

Process prescriptiveness means that ERP systems come with built-in workflows that guide how certain tasks should be performed. While this standardization ensures that companies follow efficient and tested processes, it can also be restrictive for businesses that have specialized or non-traditional workflows. Customizing these processes to better fit the company’s operations can be complex, time-consuming, and costly.

The challenge with prescriptiveness lies in balancing standardization with flexibility. While ERP vendors provide these standardized processes to streamline operations and reduce the risk of inefficiencies, organizations must assess whether the prescribed processes align with their existing practices or if they require significant adjustments. A rigid adherence to these standard processes may hinder innovation and agility, especially for companies with unique business models or those in highly competitive industries.

Resistance to Change and Custom Solutions

Change resistance is a common issue during ERP implementations. Employees accustomed to legacy systems may initially perceive the new workflows as cumbersome or unnecessary, particularly if the benefits are not immediately apparent. This resistance can hinder adoption and reduce the overall effectiveness of the ERP. In industries where business processes are a core competitive advantage—particularly in service-oriented sectors—some companies opt against off-the-shelf ERP solutions altogether. Instead, they invest in custom-developed software tailored precisely to their operational needs.

Custom solutions allow organizations to retain their unique processes without forcing employees to adapt to external workflows. Although this approach requires greater initial investment in software development, it ensures that the final system aligns perfectly with business requirements. Moreover, when stakeholders actively participate in designing the system, they develop a stronger sense of ownership, increasing long-term satisfaction and system utilization.

The decision between adopting a standardized ERP and developing a custom solution depends on several factors:

- Organizational Leadership & Change Management: Companies with strong leadership can enforce process changes more effectively, making standardized ERPs a viable option. Conversely, organizations lacking strong governance may struggle with ERP-driven transformations.

- Competitive Differentiation: If a company’s processes provide a strategic advantage, custom solutions may be preferable to avoid diluting that advantage with generic ERP workflows.

- Scalability & Maintenance: Standard ERPs offer easier scalability and lower long-term maintenance costs since vendors handle updates. Custom solutions require ongoing in-house or outsourced development, which can be resource-intensive.

- Implementation Risks: Poorly selected ERPs can lead to implementation failures if the system is too complex or misaligned with business needs. In such cases, employees may revert to old systems, negating the intended efficiency gains.

Lightweight ERPs for SMEs vs. Full-Scale ERPs for Large Enterprises

The ERP market differentiates between solutions for large enterprises and small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs):

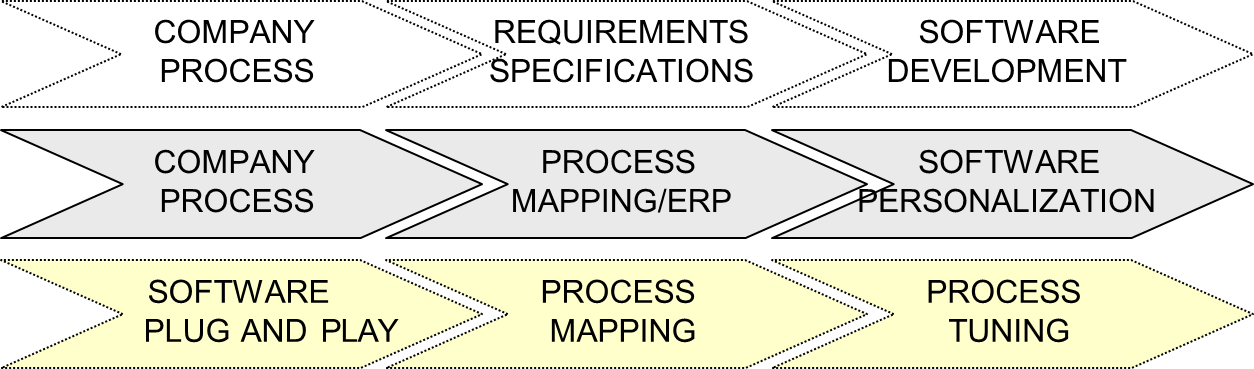

- Large Enterprises (Revenue > €50M) typically implement classic ERPs, which involve Business Process Reengineering (BPR), deep system integration, and lengthy implementation cycles (often exceeding six months). These systems support complex, cross-functional workflows but come with high costs and significant organizational disruption.

- SMEs often opt for lightweight “plug-and-play” ERPs, which focus on core administrative functions (e.g., accounting, payroll) with minimal process reengineering. While these solutions are quicker to deploy, they may lack scalability, forcing companies to migrate to more robust systems as they grow.

Cloud-Based ERP

Cloud-based ERP systems have evolved substantially since their beginnings in the mid-1990s. Originally requiring extensive on-premise infrastructure, these systems transitioned to cloud platforms as technology advanced, bringing scalability, remote access, and improved performance.

Example

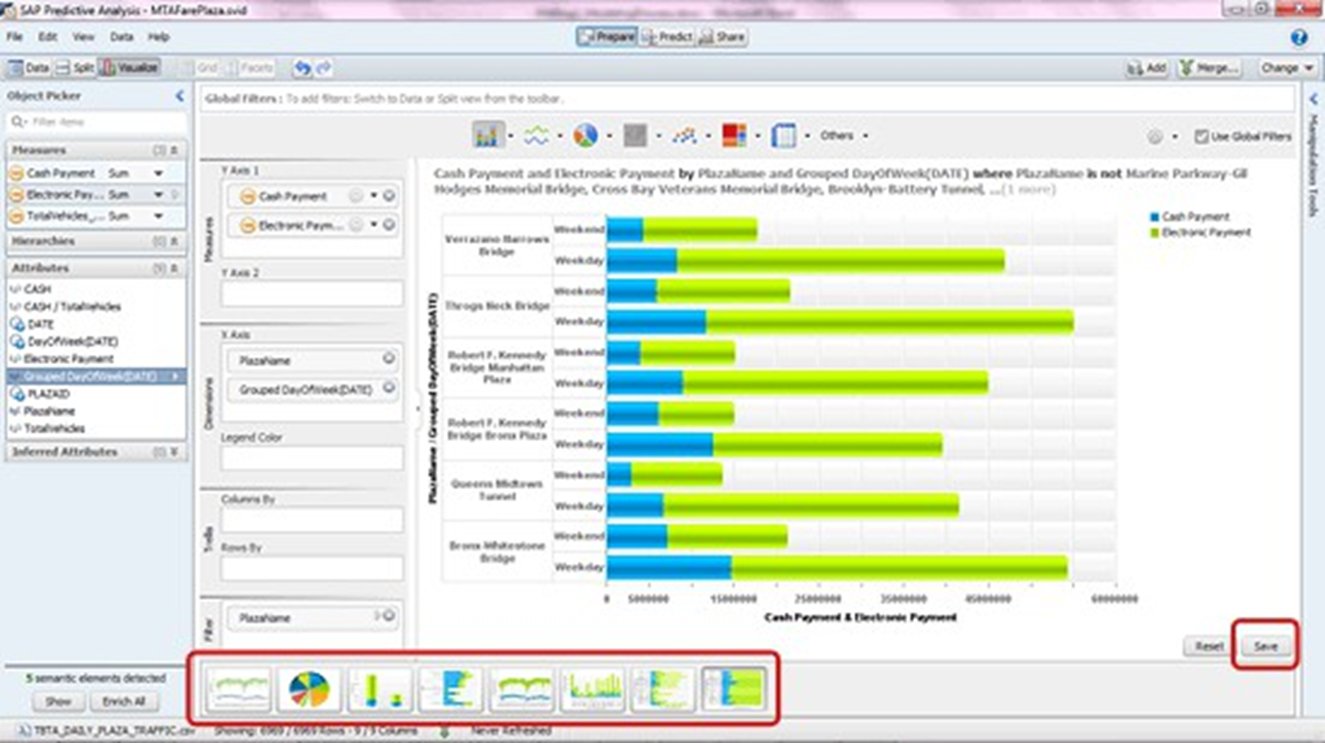

A notable example is SAP’s HANA platform, which uses an in-memory database to enable rapid data processing and real-time analytics, offering faster query responses and more efficient data management compared to traditional disk-based databases.

The interface design of cloud-based ERP systems is often utilitarian, prioritizing functionality over aesthetics. Unlike visually appealing consumer applications, these systems focus on providing essential tools for business operations. While simpler designs might lack aesthetic charm, they meet users’ need for efficiency and straightforward tools, avoiding unnecessary visual complexity. Companies have realized that intricate visualizations can sometimes detract from operational efficiency, prompting a return to basic, functional interfaces.

However, the approach shifts when addressing marketing needs. In customer-facing initiatives, visual appeal becomes crucial for communication, requiring engaging designs, infographics, and a polished user experience to convey a company’s brand and message effectively. This aesthetic focus is reserved for external projects, leaving internal ERP tools centered on functionality.

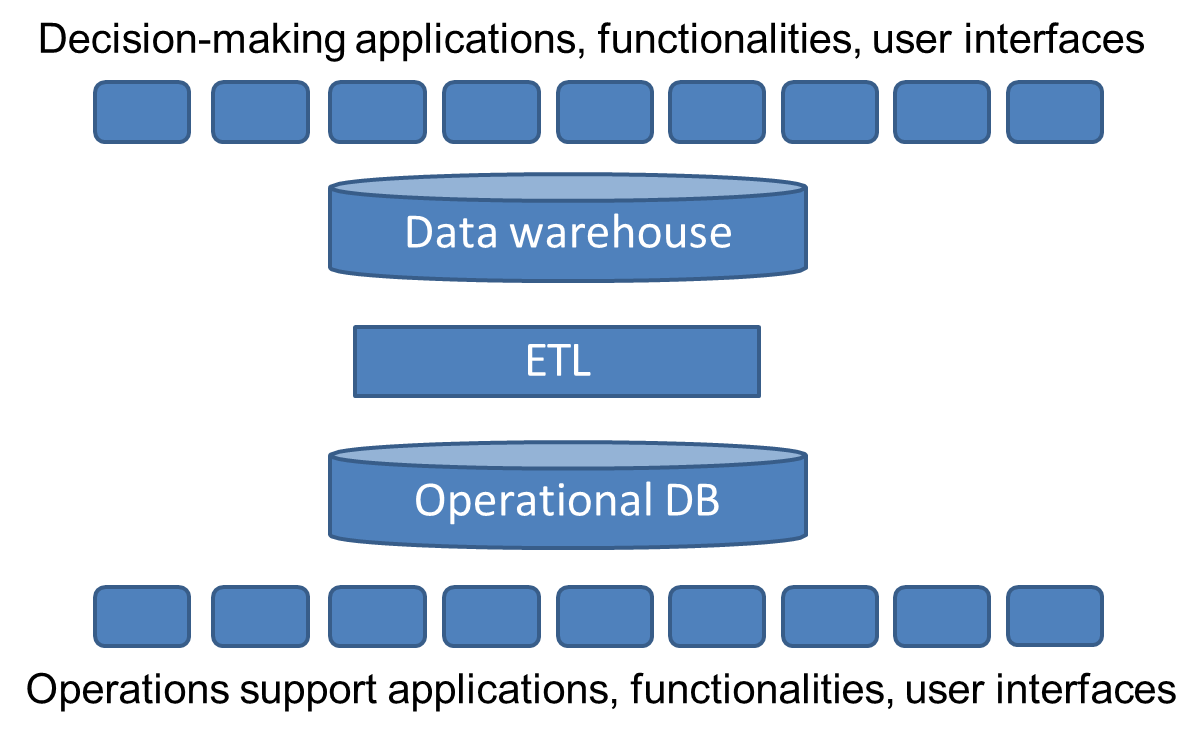

Cloud-based ERP systems also align with the broader trend of system integration, aiming to unify various business functions. These systems connect operational, executive, and administrative portfolios to facilitate data flow and support decision-making. For instance, activity-based costing (ABC) systems within ERPs improve cost tracking and resource allocation, yielding valuable insights into performance. Despite their advancements, ERP systems are still evolving toward complete integration, striving to create unified solutions that enhance operational efficiency and decision-making across diverse business areas.

ERP Integration and Innovation Strategies

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems follow a clear strategic approach centered on integration. The goal is to incorporate all necessary functionalities within a unified ERP platform. However, when innovative solutions emerge—often referred to as “extended” features—they frequently originate as independent applications. These applications may or may not be developed by the same company that created the ERP system. If an external solution proves valuable, ERP providers often acquire and integrate it into their existing suite of modules, offering a fully integrated product to the market.

This practice of acquiring and integrating third-party innovations has been prevalent for over a decade, particularly among European ERP providers, who aim to deliver a one-stop solution for businesses. A key question arises: Why do large corporations, despite having substantial Research and Development (R&D) departments, frequently rely on acquisitions rather than developing all innovations in-house?

The answer is multifaceted. While ERP vendors do invest in internal R&D, they face limitations in managing every potential innovation internally. In approximately half of cases, they opt to acquire startups or specialized software firms that have already developed successful solutions. ERP vendors often acquire startups or specialized firms because they can’t handle all innovations internally. These acquisitions are beneficial as large ERP companies have the money to invest in promising technologies, while startups are more agile, innovative, and efficient, thanks to their smaller size and lower costs. This allows startups to quickly develop and bring innovative solutions to market.

However, the startup ecosystem is highly competitive, with only a small percentage of companies surviving and scaling successfully. For those that do, acquisition by a larger firm represents a common exit strategy, providing immediate financial returns to founders and investors.

The Iterative Development of ERP Systems

The development of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems has evolved through experimentation and gradual improvement. Early efforts avoided overcomplication, focusing on creating functional prototypes known as Minimum Viable Products (MVPs). These early versions prioritized speed and cost-effectiveness over perfection, allowing for feedback-based refinement. This approach aligns with the “lean startup” methodology and principles like Google’s “permanent beta,” emphasizing continuous improvements rather than a final product.

Historically, ERP systems developed bottom-up, evolving from customized solutions for individual clients to reusable modules. Over time, these became configurable platforms that businesses could tailor without custom coding, cutting implementation timelines from years to months. ERP systems now integrate best practices and offer advanced features refined through real-world use.

Modern ERP solutions combine administrative, financial, and operational systems into unified platforms. This seamless integration and modular design result from decades of iterative improvement, balancing rapid functionality with long-term scalability.

Activity-Based Costing (ABC)

Activity-Based Costing (ABC) is an advanced costing methodology that provides a more accurate representation of costs incurred by an organization. Unlike traditional costing methods that allocate costs based on broad measures such as direct labor hours or machine time, ABC assigns costs to specific activities, ensuring a clearer picture of how resources are consumed across different operations.

The implementation of ABC requires a well-structured information system that can track activities, assign resources, and analyze cost drivers efficiently. This process involves identifying key activities, assigning costs based on actual consumption patterns, and using the resulting data for managerial decision-making.

Cash Flows and Financial Reconciliation

Cash flow refers to the movement of money in and out of a company, which is crucial for maintaining liquidity and ensuring the sustainability of business operations. It consists of two primary components:

- incoming cash flows, which result from sales, investments, or financing

- outgoing cash flows, which include payments to suppliers, salaries, and operational expenses.

To effectively manage cash flows, businesses use financial dashboards and reporting tools that provide real-time insights into their financial health. These tools help track transactions, reconcile accounts, and monitor financial performance against budgets. Integration between operational, executive, and administrative portfolios plays a key role in achieving a comprehensive view of cash flow management.

Financial reconciliation is another critical aspect, ensuring that recorded transactions match actual cash movements. This process involves cross-checking bank statements, invoices, and accounting records to identify discrepancies and prevent errors or fraud. Many organizations automate this process through enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, which streamline financial management and enhance accuracy.

Cost Control and Budgeting

One of the key objectives of financial management is cost control, which involves monitoring and reducing unnecessary expenses while maintaining operational efficiency. Budgeting is an essential tool for financial planning, allowing companies to set financial goals, allocate funds strategically, and measure performance against planned expenditures. The budgeting process typically involves estimating revenues, forecasting expenses, and setting financial targets based on historical data and market trends.

Managers must continuously review financial data to ensure alignment between planned budgets and actual expenditures. If discrepancies arise—such as higher-than-expected production costs—adjustments may be necessary to prevent overspending. This process requires collaboration between different departments, as financial decisions impact various aspects of business operations.

Tracking Costs and Activities

Understanding and reconciling cash flows with budgets, plans, and the execution of activities is a crucial aspect of financial management. This process involves three key portfolios: operational activities, planning and execution, and administrative cash flow management. One of the primary challenges in cost tracking is the inherent delay between the execution of activities and the actual cash inflows. Typically, revenues are received later than when production occurs, making it difficult to track real-time financial performance.

Example

For instance, when a company undertakes operational activities, payments from clients arrive much later, while expenses such as supplier payments and employee salaries often follow a structured schedule. Unlike insurance companies, which manage to collect payments in advance, most businesses must operate under delayed cash flows.

A fundamental aspect of cost tracking is distinguishing between actual cash flow and production expenses. Cash flows occur after the fact, meaning businesses need to establish an approach to associate costs with activities in real time. At the end of a fiscal year, companies must calculate the total cost of production by analyzing cash flows and attributions, ensuring that costs and revenues are properly assigned to the corresponding period.

The balance sheet plays a crucial role in this process. Since cash flows can be delayed by months, businesses require time—often up to six months—to consolidate all financial data before finalizing their balance sheets.

Example

For example, if a company makes a significant payment in December, but the expense is related to work for the following year, proper accounting practices ensure that the cost is attributed to the correct fiscal year.

By tracking operational portfolios—actual costs and executed activities—companies can establish clear financial records. Once the fiscal year ends, reconciling cash flows and attributing payments correctly allows for a precise balance sheet, providing insight into past expenditures. This process enables businesses to determine the exact cost of production by dividing total costs by the number of produced units, offering a clearer picture of individual product expenses.

Planning and Correcting Costs

A structured approach to cost allocation involves analyzing invoices for raw materials, supplier costs, employee wages, and managerial expenses. Different cost allocation strategies can be used, such as distributing general expenses (e.g., electricity) evenly across all produced units or applying more sophisticated methods that directly attribute component costs based on usage.

Labor costs can also be allocated using production transaction data, which tracks the time required for employees and machines to complete specific tasks. This level of detail allows companies to refine cost calculations and develop a more accurate understanding of their production expenses.

After determining actual costs, businesses can use these insights to improve financial planning for future production cycles. Comparing planned versus actual costs helps identify discrepancies and refine budget estimates.

Preventing Opportunism and Budget Overspending

Effective budget management is crucial for preventing opportunism and ensuring financial discipline within an organization. When a company allocates resources, it is essential to specify the purpose of the expenditure and track spending against the planned budget. This allows for adjustments to be made when new information becomes available, making financial data more precise over time.

Accountants analyze budgets, actual expenses, and forecasts, ensuring that spending aligns with corporate goals. The budgeting process begins with an initial allocation of funds, which is later adjusted based on actual purchase orders and expenditures. As financial data becomes more refined, different budget categories emerge, such as the original budget, the most recent cost estimate, and the final actual expenditure.

Definition

Activity-Based Costing (ABC) links costs to specific activities, providing a clear picture of how much it costs to produce a certain amount of output.

By continuously updating costs with real administrative data, companies can track expenses more accurately, reducing financial discrepancies and improving planning. This approach enables managers to integrate budgeting, operations, and financial planning into a cohesive system, fostering better decision-making in complex organizations.

In smaller businesses, financial tracking is often done manually, providing a general sense of expenditure. However, in larger corporations, financial oversight is crucial to prevent overspending and ensure accountability. Opportunistic behavior can arise when managers seek to justify higher budgets by spending excessively in the current financial cycle, hoping to secure increased funding in the future. If left unchecked, this creates a self-reinforcing loop where departments with higher expenditures receive greater allocations, while more financially disciplined units may be overlooked.

To mitigate this, organizations implement strict budget controls, ensuring that managers cannot manipulate financial allocations. Without oversight, top executives may struggle to determine how funds are utilized, relying instead on managers’ justifications. This creates a risk where the most persuasive managers secure more resources, rather than those who manage finances prudently. A continuously updated financial control system helps prevent such opportunism, ensuring transparency and accountability in financial management.

The Future of ERP Systems and Customization

A key question for businesses is whether Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems will continue evolving to serve as a comprehensive solution for all corporate needs. The answer largely depends on the company’s strategy and industry requirements. Developing custom software tailored to specific business needs is often costly and time-consuming, as companies cannot share development costs with others. Instead, ERP solutions offer a more cost-effective approach, as vendors distribute development expenses across multiple clients.

Some companies rely on ERPs exclusively for standard administrative tasks, while retaining custom-built software for critical business functions. If a particular software component is essential to a company’s competitive advantage, developing it in-house may be necessary despite the higher costs. ERPs are typically modular, allowing businesses to integrate pre-built solutions while customizing certain aspects to maintain a strategic edge.

ERPs have sustained their relevance by continuously adapting to technological advancements. When new innovations emerge, major ERP providers either develop in-house solutions or acquire startups to integrate cutting-edge capabilities. This adaptability allows ERPs to function as one-stop solutions for companies seeking convenience and efficiency.

The decision to adopt ERP solutions versus custom software mirrors the choice between shopping at a supermarket and purchasing from a specialized store. Supermarkets provide convenience by offering a broad range of products in one location, while specialized shops cater to specific, high-quality needs. Similarly, ERPs streamline operations by consolidating multiple business functions, but they may lack the flexibility of custom-built solutions.

While ERP solutions provide significant cost advantages, they also create a vendor lock-in effect. Once a company adopts an ERP system, it invests time and resources in learning and customizing it, making it difficult to switch to alternative solutions. Vendors often use this strategy to attract customers with free features, later introducing premium functionalities that require additional investment.