Why did transaction cost economics fail to accurately predict the impact of IT on organizational structures? The answer lies in agency theory, which provides a more nuanced understanding of organizational dynamics.

Agency theory criticizes the oversimplification in transaction cost economics by arguing that markets and hierarchies are not binary alternatives but rather exist on a continuum. Instead of thinking in terms of pure markets vs. hierarchies, modern organizations often blend elements of both.

For instance, large corporations integrate market-like mechanisms within their hierarchies through internal contracts, incentive structures, and decentralized decision-making. This enables them to retain the advantages of market coordination without entirely abandoning hierarchical control. Therefore, IT did not necessarily shrink organizations but allowed them to become more complex and adaptive, balancing hierarchical control with market-based interactions internally.

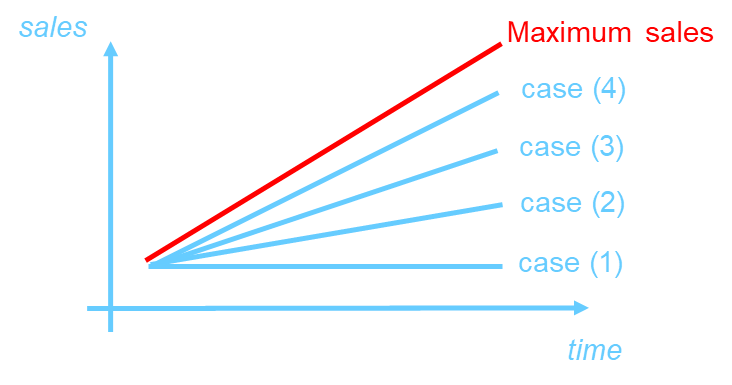

Agency theory suggests that organizations do not need to shrink to benefit from market coordination. Instead, companies can embed market mechanisms within their hierarchical structures, leveraging IT to balance efficiency and flexibility. This means that:

- Hierarchies can incorporate market coordination mechanisms—for example, firms may use internal contracts and decentralized management systems to allocate resources more efficiently.

- Market coordination mechanisms can be automated through IT—digital platforms can facilitate transactions within large corporations just as they do in the open market.

- The size of firms depends on their ability to optimize both market and hierarchical mechanisms—organizations will not necessarily become smaller; instead, they will find the optimal balance between internal coordination and market interactions.

Thus, while IT has made markets more efficient, it has also allowed large organizations to incorporate market principles internally, enabling them to scale further rather than fragment.

A key concept in agency theory is the idea of an organization as a network of contracts. Instead of viewing firms as rigid hierarchical structures, we can see them as collections of negotiated agreements that define responsibilities, incentives, and outcomes.

For example:

- An employment contract specifies what an employee must do and the compensation they receive.

- A service-level agreement (SLA) defines the terms of engagement between business units or external partners.

- Even implicit agreements, such as behavioral expectations within a company, function as contracts that guide interactions.

From this perspective, companies do not simply “grow” or “shrink” in response to IT; instead, they redefine and restructure their internal contracts to optimize performance. This allows large firms to integrate market-like flexibility within a hierarchical framework, maintaining both scale and adaptability.

In organizational theory, different market coordination mechanisms exist within organizations. One of the key perspectives that attempts to explain these mechanisms is agency theory, which has had a profound impact on organizational studies, much like the decision-making school of thought that previously revolutionized the field. Agency theory challenges traditional hierarchical structures and introduces a new way of conceptualizing organizations—not merely as production lines or closed systems, but as networks of contracts.

Organizations as Networks of Contracts

The idea of organizations as networks of contracts stems from the fundamental nature of economic transactions. In a typical transaction, there are multiple phases, including:

Phases:

- Supplier Selection: Choosing a supplier based on predefined criteria.

- Negotiation Phase: Establishing the terms and conditions of the agreement.

- Contract Formation: The result of negotiation is a service-level agreement (SLA), embedded within a broader contract that defines the execution of the transaction.

- Execution Phase: Following the agreed-upon conditions during the business interaction.

- Post-Settlement: Addressing exceptions and enforcing contractual terms when necessary.

Every stage of a transaction is governed by a contract, whether explicit or implicit. Even simple transactions, such as purchasing toothpaste at a supermarket, involve an implicit agreement: customers agree to pay before taking the product, and in return, the supermarket provides a receipt as proof of the transaction. While such agreements may not always be formally documented, they are governed by underlying regulations and norms, often detailed on a company’s website or in legal frameworks.

Thus, agency theory simplifies organizational complexity by suggesting that organizations function as a network of contracts that govern relationships, tasks, and transactions. This perspective helps in structuring workflows and defining responsibilities within companies.

Agency Theory is particularly useful in explaining how employers design contracts to align employee incentives with company goals. The fundamental challenge for employers (principals) is to ensure that employees (agents) act in the best interest of the organization. However, because employees may have different motivations, their incentives must be structured carefully.

Contracts and Employment Structures

One of the most relevant contracts within this framework is the employment contract. This legal agreement establishes the terms under which an employee engages with an employer, effectively regulating the economic aspects of the relationship. The employment contract specifies various clauses, including the salary, which dictates the economic exchange between the two parties. In this transaction, the employee provides time, skills, and expertise, while the employer compensates them with monetary remuneration. This economic exchange, in essence, defines the fundamental nature of employment relationships.

-

Fixed Salary Contracts: At the entry level, employees typically receive a fixed salary based on their role and responsibilities. This agreement specifies work hours, job duties, and compensation. While predictable, this model does not provide direct financial incentives for employees to contribute to company growth beyond their assigned duties.

-

Fixed Salary + Commission: In roles such as sales, organizations often introduce commission-based contracts, where employees earn a fixed salary plus a percentage of their sales revenue. This structure aligns the employee’s interests with the company’s success, as higher sales directly lead to higher earnings.

-

Fixed Salary + Performance-Based Bonuses: To further drive motivation, companies may offer performance bonuses. These bonuses are tied to specific performance metrics, such as achieving a predetermined sales target. Unlike a standard commission, this model introduces a threshold that employees must exceed to qualify for additional earnings, making it an effective incentive for high performance.

-

Partnership Model: At the highest level of employment contracts, companies may offer equity-based incentives, where employees become partners in the organization. This structure allows them to share in company profits rather than receiving a fixed salary. As partners, they assume entrepreneurial roles within the organization, making strategic decisions and contributing directly to company growth. This transition requires trust—a fundamental aspect of long-term organizational relationships. Companies promote employees to partnership status only when they demonstrate reliability, competence, and a deep understanding of the business.

Employee Perspective of Contracts

The primary goal of structuring these contracts is to keep employees motivated and efficient.

Organizations aim to align employee performance with entrepreneurial efficiency to drive business growth. However, achieving this is challenging because employees and entrepreneurs often have different incentives. Entrepreneurs naturally take risks for long-term growth, while employees may prioritize work-life balance.

To enhance employee commitment, organizations can restructure economic incentives within contracts. By increasing the share of benefits employees receive from business growth, employers can create a sense of ownership. This reduces a production-line mentality and engages employees in overall business performance. When employees see themselves as stakeholders, they are more invested in the company’s success.

Motivating employees toward growth is crucial for long-term competitiveness. Growth allows firms to benefit from economies of scale, enhance efficiency, and compete effectively. Stagnation risks losing a competitive edge, as larger firms have cost advantages and greater stability.

From the employee’s perspective, business growth brings challenges like increased workloads and higher expectations. Financial gains from expansion may not immediately align with the increased workload due to deferred payment cycles, especially in Italy with extended payment terms. Companies must balance financial constraints and employee motivation when pursuing aggressive growth strategies.

The Efficiency of Different Contractual Models

A well-structured contract enhances organizational efficiency by ensuring that employees operate in alignment with the company’s objectives. However, designing an effective contractual model requires balancing risk and incentives. If incentive mechanisms are too weak, employees may lack motivation; conversely, excessively aggressive incentives may encourage risky behavior aimed at maximizing individual gains.

In highly competitive environments, employees continuously evaluate alternative opportunities. Before signing a contract, they compare offers from different companies, seeking fair compensation based on market conditions and their individual skillset. This dynamic highlights the evolving nature of employment contracts, which adapt as employees gain experience and organizations grow.

From an economic perspective, entrepreneurs tend to be more motivated than employees, as they directly reap the marginal benefits of business expansion. Employees, on the other hand, rarely receive financial rewards proportional to company growth unless their contract includes specific incentive structures. Adjusting contractual terms can therefore contribute to increasing efficiency among employees.

Fixed salaries provide stability but may limit productivity, whereas commission-based models introduce incentives for exceeding minimum performance expectations. Performance bonuses serve as an additional motivational tool, as they set concrete targets for employees to achieve. Lastly, the partnership model allows employees to assume a role similar to that of internal entrepreneurs, encouraging them to contribute actively to the company’s success while sharing in the resulting financial benefits.

This evolution in contractual models reflects a progression toward greater efficiency and autonomy within organizations. The more an employee’s compensation is tied to company performance, the more their behavior aligns with that of an entrepreneur, fostering a stronger orientation toward growth and innovation.

Agency Costs

Agency costs represent an additional category of expenses that arise within hierarchical organizational structures. These costs were not explicitly considered in the framework of transaction cost economics, which primarily focuses on market-based coordination and does not address hierarchical decision-making mechanisms.

Definition

The agency cost can be defined as the total cost incurred by an organization to align employee behavior with corporate objectives. This alignment is essential for ensuring that employees act in the best interest of the company, rather than pursuing individual gains. The agency cost equation can be expressed as follows:

where:

- Control Costs: The expenses associated with monitoring and regulating employee behavior to ensure alignment with organizational goals.

- Warranty Costs: The costs incurred to establish trust and credibility between employees and the organization, ensuring that employees act in the company’s best interest.

- Residual Loss: The inefficiencies that persist despite control and warranty mechanisms, resulting from imperfect alignment between employee actions and corporate objectives.

The decision school operated under a positivistic assumption, believing decision-makers could effectively direct subordinates. This optimism overlooked the opportunistic nature of human behavior, leading to misalignment with organizational objectives and inefficiencies. Without performance-based incentives, employees may lack motivation for company growth, making the system ineffective in achieving long-term goals.

Agency costs arise from this misalignment between organizational goals and individual behavior. The decision school initially ignored these costs, assuming that employees would act in the organization’s best interest without additional incentives. In reality, aligning employee actions with business interests incurs costs through monitoring, performance-based incentives, and contract structuring.

In a hierarchical system, decision-making costs include production costs, coordination costs, and agency costs. While hierarchies provide structure, they also introduce inefficiencies due to the need for oversight and incentives. Accepting agency costs can improve efficiency and facilitate business growth, but it comes at the expense of additional costs. Organizations must balance the benefits of reduced production costs against agency costs.

Market systems are typically more efficient than hierarchies in minimizing production costs due to competitive pressures. Hierarchical structures rely on administrative mechanisms that can introduce rigidity. The challenge is designing organizational structures that minimize agency costs while maintaining coordination benefits. Firms must structure incentives, monitor performance, and distribute decision-making authority to minimize inefficiencies without excessive agency costs.

Control Costs

Control costs are a significant component of agency costs, as they encompass the expenses incurred by organizations to monitor and regulate employee behavior. These costs arise from the need to ensure that employees act in alignment with corporate goals, rather than pursuing individual interests. Control mechanisms include:

- Performance Monitoring: Organizations implement systems to track employee performance, evaluate outcomes, and provide feedback on individual contributions. Performance monitoring helps identify areas for improvement and ensures that employees remain focused on achieving company objectives.

- Reporting Structures: Hierarchical organizations rely on reporting structures to facilitate communication and decision-making. Employees report to managers, who, in turn, report to higher-level executives. This chain of command ensures that information flows efficiently throughout the organization, enabling effective coordination.

- Internal Audits: Companies conduct internal audits to assess compliance with policies, regulations, and performance standards. Audits help identify discrepancies, mitigate risks, and ensure that employees adhere to established guidelines.

Control costs are essential for maintaining accountability and transparency within organizations. By monitoring employee behavior and performance, companies can identify potential issues, address inefficiencies, and align individual actions with corporate objectives. While control mechanisms incur expenses, they are necessary to prevent agency costs from escalating and to ensure that employees contribute effectively to business growth.

Warranty Costs

Warranty costs are another critical component of agency costs, representing the expenses associated with establishing trust and credibility between employees and the organization. These costs are incurred to ensure that employees act in the company’s best interest, rather than pursuing personal gains. Warranty mechanisms include:

- Training and Development: Companies invest in employee training and development programs to enhance skills, knowledge, and competencies. Training initiatives help employees perform their roles effectively, align with organizational goals, and contribute to business success.

- Performance Incentives: Organizations offer performance-based incentives to motivate employees and reward high achievers. Incentive structures, such as bonuses, commissions, and profit-sharing plans, encourage employees to exceed expectations, drive innovation, and enhance productivity.

- Employee Engagement: Companies focus on fostering a positive work environment, promoting open communication, and encouraging employee engagement. Engaged employees are more committed, productive, and loyal, leading to higher job satisfaction and reduced turnover rates.

Warranty costs are essential for building strong relationships between employees and the organization. By investing in training, incentives, and engagement initiatives, companies can establish trust, loyalty, and mutual respect, fostering a culture of collaboration and shared success. While warranty mechanisms require financial resources, they are critical for reducing agency costs and enhancing employee performance.

Residual Loss

Residual loss represents the inefficiencies that persist despite control and warranty mechanisms, resulting from imperfect alignment between employee actions and corporate objectives. These inefficiencies can arise due to various factors, such as conflicting priorities, miscommunication, or inadequate performance management. Residual loss reflects the challenges organizations face in fully aligning employee behavior with business goals, leading to missed opportunities and suboptimal outcomes.

To minimize residual loss and reduce agency costs, companies must implement effective control and warranty mechanisms, foster open communication, and promote a culture of accountability and transparency. By addressing the root causes of inefficiencies and enhancing employee engagement, organizations can mitigate residual loss, improve performance, and drive long-term growth. While residual loss may never be entirely eliminated, proactive measures can help organizations minimize its impact and maximize operational efficiency.

Hierarchical Control in Market Systems

In perfect market systems, customers have little to no control over their suppliers. These markets function best when there is a high level of trust, and transactions between businesses are fully delegated. This means that suppliers and customers operate with minimal intervention or influence from one another, creating an idealized free-market environment where each party operates independently. However, when markets are imperfect—such as those characterized by less competition or greater interdependence—the relationship between customers and suppliers changes significantly. In these scenarios, customers may exert some control over their suppliers, sometimes through hierarchical forms of management that influence the production process. This form of control allows customers to ensure that suppliers meet certain standards, follow specific procedures, and deliver goods or services in a way that aligns with the customer’s business objectives.

In these non-perfect market systems, there is often a complex overlap between market transactions and hierarchical forms of control. This overlap can be seen in various management programs and business practices, such as Total Quality Management (TQM) initiatives, process inspections, cooperative information systems, joint ventures, and even controlled start-ups. These examples highlight how companies, even in competitive market environments, can create relationships that incorporate elements of hierarchy to enhance their control over suppliers or service providers.

A pertinent question arises: Is it possible to have hierarchical control within market systems? The answer is affirmative. A clear example of this can be seen in certain industries or geographical regions where a single, dominant company exerts substantial influence over its suppliers, even though they maintain their formal independence. These companies may not necessarily be monopolies, but they are powerful enough to dominate a specific sector or local market, shaping the operations of their suppliers in ways that resemble hierarchical control. The dominant company often imposes its terms on the suppliers, determining aspects such as pricing, production processes, and even labor conditions. This situation occurs when a company’s size and influence allow it to dictate the terms of engagement, even when suppliers are technically independent businesses.

This form of hierarchical control brings with it certain advantages for the dominant company, particularly in terms of flexibility. Unlike employees, suppliers do not have the same legal protections or labor union support, meaning the company is not burdened with the costs and complexities of layoffs during periods of decreased demand. If demand drops, the company simply stops placing orders with its suppliers, avoiding the need for the long-term commitments and costs associated with maintaining a large, permanent workforce. This model provides a company with the agility to scale up or down quickly in response to market conditions, without the operational risks tied to employee turnover or labor disputes.

Despite their formal independence, many suppliers in these market systems find themselves economically dependent on the dominant company, often to the point where their survival hinges on securing orders from a single client. This situation is more common than it may seem, especially in sectors like fashion, where small, independent contractors or businesses rely heavily on larger brands for their livelihood. These suppliers are often referred to as “fastons,” a term used to describe highly skilled, independent tailors or workers who experience fluctuating work patterns depending on demand. While these workers enjoy the flexibility of setting their own schedules and earning good money during periods of high demand, they also face the significant downside of job insecurity.

From the perspective of the dominant company, this model offers clear advantages, as it allows for rapid growth or contraction without the constraints of managing a large, permanent workforce. When market conditions change, the company can quickly adjust by increasing (or decreasing) the number of orders placed with suppliers, which is far simpler than dealing with the complexities of layoffs and workforce management. This dynamic is evident during crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when dominant companies were able to prioritize their own survival over that of their suppliers, often to the detriment of smaller, independent businesses. These suppliers, however, were able to recover as the market stabilized, showcasing the adaptability of the hierarchical control structure in market systems.

The Role of IT in Organizational Structures

While hierarchical control is an important factor in managing supplier relationships, the integration of information technology (IT) has transformed how companies implement and enforce these relationships. Information technology plays a crucial role in streamlining operations, providing companies with the tools to coordinate complex relationships with suppliers, and improving decision-making capabilities. Traditional Business Information Systems (BIS) were initially designed to help companies manage their internal operations, but over time, IT systems have evolved to support interactions with external suppliers as well. Today, these systems help coordinate everything from supply chain logistics to financial transactions, enabling companies to maintain control and oversight over their suppliers even as they interact within a broader market environment.

Theories of organizational management suggest that the proper use of technology can flatten organizational hierarchies, empowering lower levels of management and speeding up decision-making. In theory, the use of advanced information systems should make a company more agile, allowing it to respond quickly to shifts in market demand, improve operational efficiency, and enhance customer satisfaction. As a result, many companies are increasingly relying on IT systems that allow them to leverage large amounts of data, make predictive analyses, and better understand trends that could impact their supply chains or customer demands.

The Stability of Software in Business Environments

Another key element in the relationship between technology and hierarchical control in market systems is the stability of software solutions. Developing and maintaining software systems is a complex and costly endeavor. Once a system is proven to function reliably, businesses are often hesitant to replace it with a new solution. Instead, companies tend to build new functionalities or technologies around the existing systems. This approach is evident in technologies like Docker, which enables old software systems to function in modern IT environments. Many companies continue to use legacy systems because they provide immediate results without requiring extensive retraining or the steep learning curve that comes with new tools.

Example

For example, Microsoft Excel, despite being a decades-old software, remains widely used in businesses worldwide. It is not the most advanced tool available, but its simplicity and user-friendliness make it indispensable for many businesses. Similarly, more flexible, coding-based solutions may offer greater functionality, but the need for specialized programming expertise limits their widespread adoption. As a result, many businesses continue to operate with legacy systems while simultaneously integrating new technologies that complement these older platforms.

Limitations of Agency Theory in Organizational Decision-Making

Agency theory is often used to analyze the relationship between principals (such as business owners or shareholders) and agents (such as managers or employees) in an organizational context. However, it has several limitations when applied to real-world market and hierarchical structures, particularly in the modern era of information technology.

One key limitation of agency theory is that it does not provide a definitive answer to whether markets will become more dominant than hierarchies or vice versa. The balance between market mechanisms and hierarchical control depends heavily on the nature of tasks within a specific industry. In theoretical terms, agency theory suggests that the structure of an organization depends on the complexity and specificity of tasks. However, it does not explicitly define how different industries should be structured based on their unique operational needs. This gap makes it challenging to apply agency theory uniformly across various business sectors.

Another critical shortcoming of agency theory is its lack of consideration for the role of information technology in shaping modern organizations. The foundational principles of agency theory were developed before the widespread adoption of digital technology and automation. As a result, while the theory provides a useful conceptual framework for understanding organizational behavior, it does not offer practical guidance on how technology can influence agency relationships, reduce agency costs, or improve decision-making processes.

To understand how information technology impacts organizational structures, we must turn to a different field known as Management Information Systems (MIS). Unlike agency theory, which focuses on abstract economic relationships, MIS explores how digital tools and enterprise systems influence decision-making, coordination, and control within organizations. This field examines how technology enables firms to delegate responsibilities efficiently while maintaining oversight through automated monitoring, predictive analytics, and data-driven management techniques.

The Challenge of Balancing Theory and Practice

In business research, there is always a tension between theoretical models and practical applications. While abstract theories help identify fundamental principles, they often fail to provide actionable solutions for real-world business challenges. To bridge this gap, organizations must rely on case studies and empirical research to identify patterns and extract generalizable lessons.

Case studies are essential because they allow us to observe how different firms implement delegation, decision-making, and control in practice. If we only rely on theoretical models without studying actual business implementations, we risk lacking cumulative knowledge that builds upon real-world experiences. Therefore, management research must continuously refine theoretical models by incorporating insights from practical applications.

Delegation and Middle Management

One consequence of delegation in hierarchical organizations is the emergence of middle management layers. When direct supervision becomes impractical, firms often introduce project managers or team leaders who act as intermediaries between top executives and operational employees. This structure ensures that decision-making authority is distributed across different levels of the organization, preventing bottlenecks at the executive level.

However, the expansion of middle management also introduces inefficiencies. If a company becomes overly dependent on managerial oversight, decision-making can become slow and bureaucratic. This is particularly problematic in large-scale enterprise projects, where multiple layers of management may exist solely to coordinate activities without directly contributing to the work itself. As a result, businesses must carefully balance delegation with efficiency to prevent excessive administrative overhead.

The Evolution of Hierarchical Control in the Digital Era

In the past, hierarchical organizations relied on manual processes to coordinate activities. Managers exercised control through direct supervision, regular meetings, and structured reporting. However, with advancements in business intelligence (BI) tools, artificial intelligence (AI), and automation, companies can now implement decentralized decision-making structures that are both efficient and scalable.

For example, modern agile organizations use data-driven decision-making to enable autonomous teams to operate with minimal managerial oversight. This shift reduces reliance on traditional hierarchical control while still maintaining accountability through real-time performance tracking. Consequently, digital transformation has led to a redefinition of agency relationships, challenging traditional assumptions about control and delegation in organizations.

Conclusion

Agency theory provides a useful foundation for understanding principal-agent relationships, but its limitations become evident when applied to modern, technology-driven organizations. The theory does not account for the transformative role of information systems, automation, and digital platforms in reshaping hierarchical structures and delegation strategies.

To fully grasp the dynamics of contemporary business environments, we must complement agency theory with insights from management information systems, organizational behavior, and technology management. By integrating theoretical perspectives with empirical research, we can develop a more comprehensive understanding of how businesses navigate the complexities of delegation, control, and efficiency in an era defined by digital innovation.