The Agile methodology is a modern approach to software development that emphasizes flexibility, collaboration, and iterative progress. At the heart of Agile lies the concept of managing a product backlog: a dynamically ordered list of all the features, improvements, bug fixes, and technical tasks that define the scope of the project. This backlog is constantly updated and prioritized to reflect the evolving needs of the client and stakeholders.

The responsibility for defining the priorities within the backlog does not fall on the development team but rather on a key figure known as the Product Owner, who collaborates closely with the development team, providing them with a clear understanding of the business context and user needs.

This role is critical to Agile’s success because it separates the strategic planning of what to build from the tactical responsibility of how to build it. The team focuses solely on delivering high-quality implementations of the chosen features, without needing to decide which are the most business-critical. This separation of concerns allows for better accountability and traceability, especially when clients question why certain features were prioritized over others.

Continuous Client Involvement and Feedback Loops

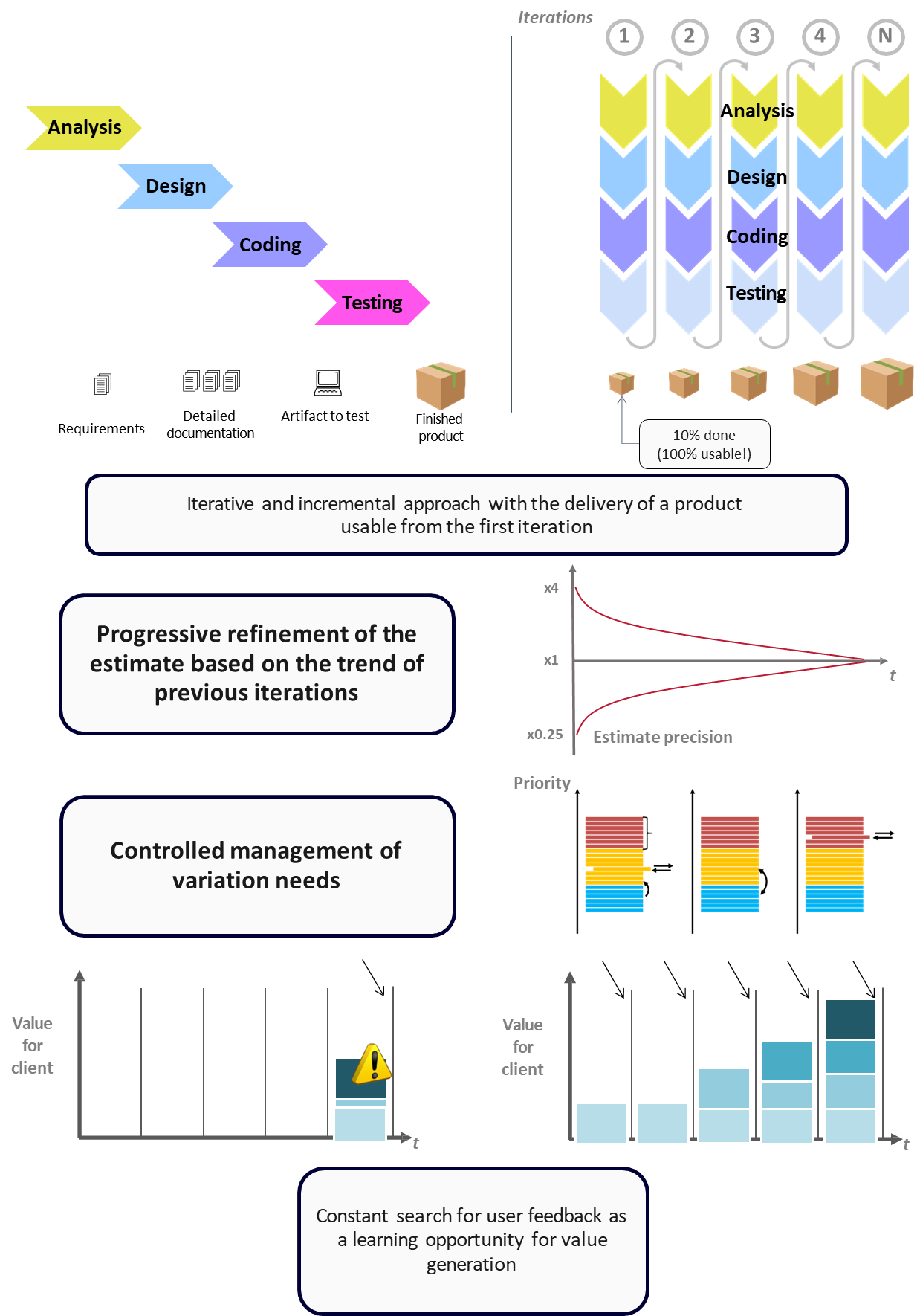

A fundamental difference between Agile and traditional methodologies lies in how and when client feedback is integrated.

- In the Waterfall model, clients are often involved only at the beginning and end of the project, leading to a disconnect between their expectations and the final product.

- In contrast, Agile emphasizes continuous client involvement throughout the development process. This is achieved through regular feedback loops, where the development team demonstrates working software to stakeholders at the end of each iteration.

This iterative approach allows for real-time adjustments based on client feedback, ensuring that the final product aligns closely with their needs and expectations.

The Agile methodology is built on the principle of empirical process control, which emphasizes the importance of transparency, inspection, and adaptation. By involving clients in the development process, Agile teams can gather valuable insights and feedback that inform their decisions and help them course-correct as needed.

Agile corrects this flaw by embedding the client (through the Product Owner) into the development cycle. After every iteration (typically lasting one to four weeks), the team delivers a potentially shippable product increment, which is demonstrated to stakeholders. This real-time visibility into progress enables stakeholders to validate outcomes early and often. Moreover, by involving actual users in the feedback process, Agile ensures that the product evolves to meet real-world needs, not just assumptions.

Another important tool in Agile for validating correctness is the user acceptance test (UAT). These are predefined functional tests agreed upon by the client and development team to validate that a given feature works as intended. UATs serve as objective proof that a user story is “done,” according to agreed criteria.

Contracts and the Agile Mindset

Agile-aligned contracts prioritize collaboration, shared objectives, and mutual understanding over strict compliance with rigid specifications. This collaborative model fosters a more effective and resilient partnership, facilitating the joint navigation of the complexities inherent in software development.

Several contractual models illustrate varying degrees of alignment with Agile principles:

- Fixed-Price Contracts entail a predetermined payment for a specified set of deliverables, regardless of the actual effort involved. While this model offers predictability in budgeting, it often results in conflict when unforeseen technical challenges arise or when client expectations shift mid-project.

- Time and Materials Contracts are structured around compensation for actual time and resources expended. This model inherently supports Agile methodologies, as it permits iterative progress and the incorporation of real-time client feedback.

- Cost-Plus Contracts involve reimbursing the development team for actual costs incurred, supplemented by a fixed profit margin. This approach balances flexibility with incentives for efficiency, aligning well with Agile’s adaptive framework.

- Value-Based Contracts tie compensation to the business value delivered rather than to resource expenditure. This model aligns most closely with Agile principles, emphasizing the delivery of outcomes that are meaningful to the client and accommodating scope evolution throughout the project lifecycle.

Traditional Waterfall-based approaches typically fix the scope, budget, and timeline at the project’s inception. The development team is then expected to deliver the complete set of predetermined functionalities within these constraints. Such rigidity often leads to unrealistic expectations and friction when changing requirements or unforeseen obstacles emerge. Agile development, conversely, reconfigures this paradigm by fixing the budget and timeline while allowing the scope to remain fluid. Within these financial and temporal constraints, the development team prioritizes and delivers the most valuable features. This ensures that clients receive the highest-impact functionality early, even if less critical features are deferred or omitted altogether. The focus, therefore, transitions from comprehensive delivery to the delivery of strategically significant features.

This approach is particularly advantageous in fast-paced, competitive markets, where reducing time-to-market is often a critical determinant of a product’s success. Releasing a refined subset of features expediently is typically more valuable than delaying release in pursuit of completeness, which may ultimately prove obsolete by the time of deployment.

Agile development is budget-driven, not scope-driven. Clients provide a budget and vision, and the team delivers the most critical functionalities iteratively, enabling early user engagement and feedback. Initial iterations often focus on core capabilities, establishing deployment, monitoring, and maintenance practices. This incremental approach fosters operational familiarity and sustainable scaling.

Each Agile iteration aims to produce potentially deployable software, even during infrastructure-focused phases. Avoiding throwaway code is crucial to prevent technical debt, which can hinder maintainability and scalability. Agile teams mitigate this by adhering to a shared Definition of Done (DoD), which includes criteria like automated testing, peer reviews, documentation, and high test coverage (e.g., 95% for critical components). This ensures quality and long-term system stability.

Why Agile Methodology Today?

The need for Agile methodologies today stems from the increasing complexity and dynamic nature of modern projects, particularly in software development, where traditional models often struggle to accommodate changing requirements and rapid feedback. Despite its benefits, Agile adoption, especially in large organizations, faces significant barriers. A key challenge is organizational resistance, as Agile often flattens hierarchies and promotes direct communication, potentially threatening traditional middle management roles centered on static processes and document-driven planning.

Implementing Agile is not merely adopting new tools or processes but requires a cultural shift and a new mindset embracing uncertainty, collaboration, and incremental delivery. Many organizations fail because they claim to “do agile” without truly adopting this underlying cultural change, maintaining old habits.

The Agile movement originated from lean manufacturing principles pioneered by Toyota, which emphasized iterative processes, empowered teams, and customer value. Inspired by this, a group of software professionals created the Agile Manifesto in 2001, adapting lean thinking to software development by prioritizing working software, collaboration, and responsiveness to change over comprehensive documentation, contract negotiation, and rigid plans.

A central idea in Agile is embracing change. Evolving requirements are viewed not as threats but as valuable insights informing project direction. Instead of rigid adherence to initial plans, Agile teams maintain a flexible product backlog that adapts based on new information and priorities. Delivering value incrementally ensures that useful outcomes are achieved even if projects face early termination or budget constraints. Finally, Agile promotes transparency and team ownership. Everyone involved, from developers to product owners, participates in planning and decision-making, fostering shared responsibility, more realistic expectations, and higher team morale.

Agile Manifesto

The Agile Manifesto is a foundational document that outlines the core values and principles of Agile software development. It emphasizes the importance of

Quote

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

The manifesto serves as a guiding framework for Agile teams, encouraging them to prioritize these values in their work. The Agile Manifesto is built on 12 principles that further elaborate on its core values. These principles include:

Quote

- Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

- Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

- Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference for the shorter timescale.

- Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.

- Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

- The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.

- Working software is the primary measure of progress.

- Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.

- Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility.

- Simplicity—the art of maximizing the amount of work not done—is essential.

- The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

- At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

These principles guide Agile teams in their day-to-day work, helping them to create high-quality software that meets customer needs while remaining adaptable to change.

Scrum

Definition

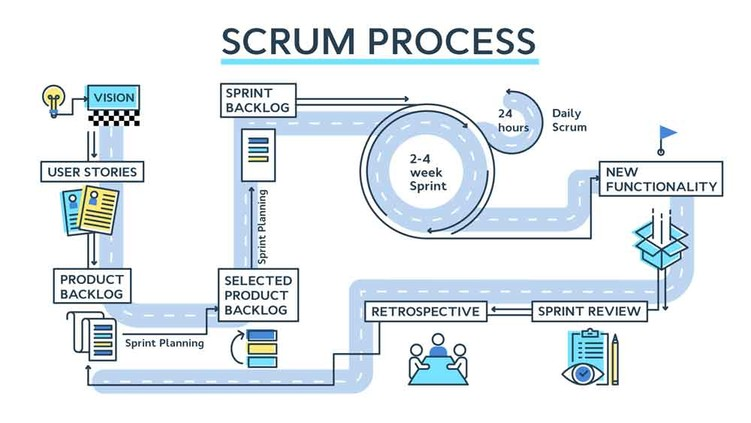

Scrum is a lightweight framework within the Agile methodology designed to help teams work collaboratively and deliver value incrementally. It provides a structured approach to managing complex projects by breaking them into smaller, manageable iterations called Sprints, which typically last one to four weeks.

At its core, Scrum emphasizes transparency, inspection, and adaptation. Teams operate with clearly defined roles and follow a set of “ceremonies”, such as Sprint Planning, Daily Scrum, Sprint Review, and Sprint Retrospective. These events ensure continuous alignment, foster collaboration, and allow for iterative improvements.

Scrum’s iterative nature enables teams to deliver potentially shippable product increments at the end of each Sprint. This approach ensures that stakeholders can provide feedback early and often, reducing the risk of misaligned expectations and enabling the product to evolve in response to real-world needs.

3 Roles in Scrum

In Scrum, three core roles form the backbone of the development process:

- the Product Owner

- the Development Team

- the Scrum Master

Each role holds distinct responsibilities and contributes uniquely to the overall success of a project.

| Role | Primary Focus | Key Responsibilities | Authority Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Owner | Maximizing product value | Managing the Product Backlog, prioritizing features, defining acceptance criteria | High authority over backlog prioritization, but no direct control over the Development Team |

| Development Team | Delivering potentially shippable increments | Implementing backlog items, adhering to the Definition of Done, self-organizing | Full autonomy over how to execute work within a Sprint, accountable for delivering agreed outcomes |

| Scrum Master | Facilitating the Scrum process | Coaching the team, removing impediments, ensuring adherence to Scrum principles | No formal authority; acts as a servant-leader to guide and support the team |

The Product Owner

Definition

The Product Owner acts as the representative of the customer and holds the ultimate responsibility for the value generated by the product.

While this role may initially appear similar to that of a traditional Project Manager, there are critical differences in their scope and influence.

- The project manager typically oversees the entire project lifecycle, including timelines, budgets, and team performance across multiple projects.

- The Product Owner, on the other hand, focuses exclusively on the product itself, defining and prioritizing features based on business value and stakeholder needs.

The Product Owner maintains and curates the Product Backlog, which serves as the single source of requirements for the development team. This role involves constant collaboration with stakeholders to capture evolving needs and translate them into user stories or backlog items. However, once a Sprint begins, the Product Owner cannot make unilateral changes to its content. This stability ensures that the Development Team can focus on delivering the committed work without disruption.

Importantly, the Product Owner must possess both vision and decisiveness. They have the authority to reorder backlog items, cancel a sprint in rare critical cases, and re-evaluate priorities based on new business insights. However, this authority is bounded: during the Sprint, the team operates independently, and the Product Owner is not allowed to interfere directly with its work.

In the ideal setup, the Product Owner should be the actual client or end-user, as this ensures that decisions are grounded in real business value. However, in practice, the Product Owner is often an internal representative who collaborates with the client, translating business requirements into a development context.

The Development Team

Definition

The Development Team is a self-organizing and cross-functional unit typically composed of 3 to 9 individuals, that collectively own the responsibility of turning the Product Backlog into working, potentially shippable increments of software at the end of each Sprint.

The term “developer” in this context is broad and inclusive; it refers not just to programmers, but to designers, testers, UX experts, and anyone else contributing to the product increment.

The size limitation of Scrum teams is intentional. Teams larger than 9 people tend to suffer from communication overhead and reduced agility. Coordination becomes inefficient, and decision-making is delayed. For larger-scale projects involving dozens of developers, frameworks like LeSS (Large Scale Scrum) extend the principles of Scrum to multiple teams by introducing coordination layers such as Scrum-of-Scrums.

Development teams in Scrum are self-managing. They have the autonomy to decide how to implement the work selected for a Sprint. This includes choosing the architecture, technologies, and task distribution.

The Scrum Master

Definition

The Scrum Master serves more as a facilitator, coach, and guardian of the Scrum process. This role requires a deep understanding of Agile principles and the ability to navigate team dynamics and interpersonal relationships.

The Scrum Master is responsible for the process

- helping the team to understand and implement Scrum practices effectively and ensuring that the Scrum framework is followed and that the team adheres to its values and principles.

- facilitating Scrum events such as Sprint Planning, Daily Scrum, Sprint Review, and Sprint Retrospective.

- removing impediments that may hinder the team’s progress and organizing the team’s work environment, protecting it from external distractions and interruptions and fostering a culture of collaboration and accountability.

- facilitating communication between the team and the Product Owner, as well as with external stakeholders.

5 Scrum Events

In Scrum, the concept of time-boxed iterations is central to managing the development process in an Agile environment. Each Sprint is a fixed-length event during which a potentially shippable product increment is developed. The typical duration of a Sprint ranges from 1 to 4 weeks, with 2 weeks being the most commonly adopted standard across various teams and organizations.

- 2-week Sprints are often preferred because they strike a balance between providing enough time for meaningful work to be completed while still allowing for frequent feedback and adaptation. This duration is manageable for most teams, enabling them to maintain focus and momentum without becoming overwhelmed by the complexity of longer iterations.

- 3/4-week Sprints can be beneficial for teams that have a high level of experience and familiarity with the project domain, as they allow for deeper focus on complex tasks without the frequent interruptions of shorter iterations.

- 1-week Sprints are often used in early-stage projects or when the team is still forming, as they provide a higher level of visibility and allow for rapid feedback and adaptation to changing requirements

The Scrum framework is built around five key events, each serving a specific purpose in the development process. These events are:

- Sprint Planning: A formal event that marks the beginning of each Sprint, where the team collaborates with the Product Owner to select items from the Product Backlog and establish a clear Sprint Goal.

- Daily Scrum: A brief, focused meeting that occurs daily to synchronize the team’s efforts and surface any impediments as early as possible.

- Sprint Review: A collaborative working session at the end of the Sprint where the team presents the increment to the Product Owner and other stakeholders, allowing for feedback and adjustments.

- Sprint Retrospective: A structured opportunity for the Scrum Team to reflect on the just-completed Sprint, identifying areas for improvement in processes, collaboration, and technical practices.

- Backlog Refinement: An informal meeting dedicated to analyzing, breaking down, estimating, and improving the clarity of the Product Backlog items (PBIs).

Sprint Planning

Sprint Planning is a formal event that marks the beginning of each Sprint. It defines what the Development Team will work on during the upcoming iteration. Under ideal conditions, this meeting is held once per Sprint and can last up to several hours, depending on the Sprint length. The team collaborates with the Product Owner to select items from the Product Backlog and establish a clear Sprint Goal.

However, in some cases—especially when teams are inexperienced, unfamiliar with the domain, or lacking in estimation skills—Sprint Planning must be adjusted.

Example

A notable example involves teams that are unable to reliably forecast beyond a single day. In such situations, Sprint Planning may be reduced to a daily planning cycle, where work is planned every morning and reviewed in the evening. This extreme form of short-cycle planning typically emerges in high-uncertainty contexts, where requirements change rapidly and software designs evolve mid-iteration.

As the team gains familiarity with the codebase, domain, and development tools, their ability to estimate improves. With this maturity, the Scrum Master may gradually increase Sprint duration—moving first to weekly cycles, and eventually to bi-weekly Sprints once stability is achieved. The key is to align the planning frequency with the team’s capacity to forecast accurately and execute consistently.

Daily Scrum

The Daily Scrum, or daily stand-up, is a brief, focused meeting that usually occurs at the beginning of the workday, typically between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m. Its purpose is to synchronize the team’s efforts and surface any impediments as early as possible. Although the recommended time-box for this meeting is 15 minutes, in practice it often runs longer when not properly facilitated.

The structure of the Daily Scrum typically revolves around three guiding questions:

- What did I accomplish yesterday?

- What will I do today?

- Are there any impediments in my way?

A particularly valuable dynamic of the Daily Scrum is its role in surfacing hidden impediments early. Without this daily checkpoint, developers may go unnoticed for several days while struggling in isolation, only to admit failure at the end of the Sprint. The Scrum structure eliminates this pattern by requiring individuals to speak up daily, thereby distributing accountability evenly across the team.

The Scrum Master plays a crucial role in facilitating the Daily Scrum, and its a good practice to designate this role to a member of the team that is not directly involved in the discussion. This ensures that the meeting remains focused and efficient, allowing team members to share their updates without distractions. The Scrum Master is not a contributor to the software product but rather a facilitator of the process and a servant-leader to the team.

Sprint Review

The Sprint Review marks the conclusion of a development iteration and serves as a critical checkpoint to assess the outcome of the work performed in relation to the Sprint Goal. During this event, the Scrum Team presents the increment—i.e., the potentially shippable product increment that was developed over the sprint—to the Product Owner and other relevant stakeholders. This session is not merely a status update but a collaborative working session where the team demonstrates the new features or changes introduced during the sprint.

The Product Owner has the authority to accept or reject completed work based on the acceptance criteria and the alignment with the Sprint Goal. This direct feedback mechanism often leads to the emergence of new requirements or the modification of existing ones, as this may be the first time the Product Owner sees a concrete implementation. This dynamic underscores the iterative and adaptive nature of Scrum, where changes are welcomed—even late in development—to maximize value.

One of the key advantages of the Sprint Review is its early feedback loop, contrasting significantly with traditional Waterfall approaches. In a Waterfall model, teams may operate in silos for months before stakeholders see any outcome. In Scrum, however, stakeholders provide feedback every two weeks (or after each sprint), allowing the team to pivot or adapt promptly. This event is also an opportunity for external stakeholders to ask questions and raise concerns, though decision-making remains the responsibility of the Product Owner.

Sprint Reviews are typically scheduled toward the end of the sprint, often on a Friday morning, and are organized by the Scrum Master. These reviews not only foster transparency but also boost team morale, as developers gain visible acknowledgment of their progress and see the project taking shape in tangible ways.

Sprint Retrospective

The Sprint Retrospective is held shortly after the Sprint Review, often on Friday afternoon, and is a structured opportunity for the Scrum Team to reflect on the just-completed sprint. Its primary purpose is to identify areas for improvement in terms of processes, collaboration, tooling, and technical practices. Unlike the Review, which focuses on the product, the Retrospective targets the team’s internal functioning and performance.

During this session, each team member can openly discuss what went well, what did not, and what could be improved. This includes raising concerns about technical debt, inadequate collaboration, lack of clarity in requirements, or ineffective tooling. However, the aim of the meeting is not necessarily to solve problems on the spot. Instead, identified issues can be transformed into actionable improvement items (or process-level user stories) and subsequently added to the Product Backlog.

These improvement items are then prioritized and owned by the team, but their execution is subject to the Product Owner’s approval. While the team may advocate for better tooling, refactoring, or investment in upskilling, only the Product Owner can allocate sprint capacity to these items. If the Product Owner repeatedly rejects such items, they bear the accountability for any productivity losses, as they chose not to invest in improving the team’s development process.

This meeting encourages continuous improvement and enforces Scrum’s pillar of inspection and adaptation. It also helps eliminate toxic behaviors or unproductive team dynamics by fostering psychological safety and transparency. As a best practice, the Scrum Master should ensure that the meeting remains focused, inclusive, and constructive.

Backlog Refinement

The Backlog Refinement (previously known as “Grooming”) is another essential, although informal, Scrum event. This meeting is dedicated to analyzing, breaking down, estimating, and improving the clarity of the Product Backlog items (PBIs). Unlike other Scrum ceremonies, refinement is the only event where detailed discussion about scope, dependencies, and technical feasibility is not only allowed but encouraged.

This meeting may last several hours—typically ranging between four and eight—especially when refining items for complex products. While theoretically the entire Scrum Team should be involved in the refinement process to preserve shared understanding, in practice, some organizations limit participation to senior developers or rotating representatives from each team to improve efficiency. However, this trade-off may result in a loss of shared context over time, which can affect estimation accuracy and the quality of implementations.

A core objective of backlog refinement is to ensure that user stories are “ready” for implementation in the next sprint. A common mistake in immature teams is to include poorly defined or ambiguous stories in the Sprint Backlog. This leads to implementation delays, constant clarification requests, and scope instability. To avoid this, teams should define a “Definition of Ready”—a checklist of criteria that a backlog item must meet to be considered actionable. Similarly, the “Definition of Done” ensures that completed work meets the quality and completeness standards established by the team.

Backlog refinement also allows the Product Owner to reprioritize items, add new requirements, remove obsolete ones, or adjust the scope in response to emerging insights. For example, if the team encounters unexpected complexity during development, items may be descaled or deferred to preserve the sprint timeline. As with other aspects of Scrum, the Product Owner holds full accountability for these scope decisions, and their implications on the delivery schedule are transparently communicated and owned.

3 Artifacts

In Agile frameworks, particularly Scrum, specific artifacts serve to make work and value transparent. These artifacts provide critical information for planning, executing, and inspecting progress.

The Product Backlog stands as a fundamental artifact, representing a dynamic, ordered list of everything that is known to be needed in the product. This list serves as a single source of requirements for any changes to be made to the product. Items within the Product Backlog are ordered based on their business value, risk, dependencies, and other factors deemed important by the Product Owner, who is accountable for the Product Backlog’s content, availability, and ordering. Items higher in the backlog, signifying greater value or priority, require more detailed descriptions to enable the development team to understand, estimate, and ultimately develop them within a single Sprint. The continuous evolution of the product, driven by changing market conditions, customer feedback, and emerging needs, necessitates that the Product Backlog is a living document, constantly refined, updated, and re-prioritized.

To articulate the needs captured within the Product Backlog, items are frequently expressed in the form of User Stories.

Definition

A User Story is a concise, high-level description of a desired piece of functionality from the perspective of the end-user, customer, or stakeholder. The common format, “As a [type of user], I want [an action] so that [a benefit],” helps to focus on the value delivered. User Stories can be broadly categorized:

- Functional stories detail specific use cases and required features that the system must perform.

- Non-functional stories, often technical in nature and sometimes written by the development team, address technical requirements such as performance, security, scalability, and maintainability.

- Consolidation and maintenance stories encompass activities like bug fixes, refactoring, and fine-tuning existing functionalities to improve the product’s quality and stability.

A key characteristic of effective User Stories is their focus on what is needed and why, rather than prescribing how it should be implemented, thus avoiding premature solutioning. They must provide sufficient detail to be understood and estimated by the team, striking a balance between brevity and comprehensiveness while ideally using business-oriented language rather than technical jargon where possible. These stories serve to elaborate upon the items listed in the Product Backlog, making them actionable for the development team.

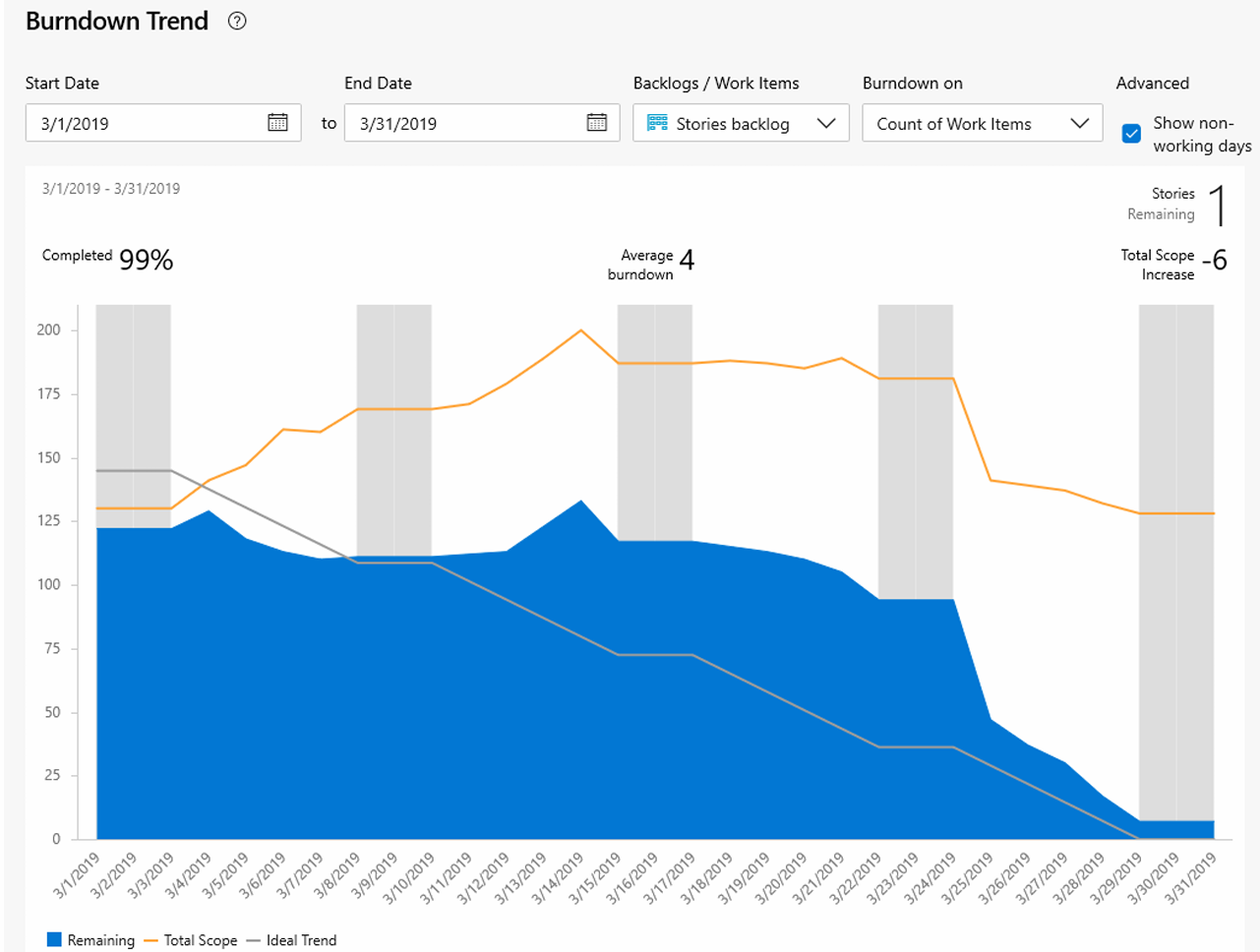

The Sprint Backlog is a forecast by the Development Team about what functionality will be in the next Increment and the work needed to deliver that functionality. It is derived from the Product Backlog and represents the set of Product Backlog items selected by the Development Team for the current Sprint, along with the plan for delivering the Increment and realizing the Sprint Goal. The team’s capacity, often informed by historical performance data (velocity) from previous Sprints, guides the selection of items. Once items are selected, the Development Team collaboratively breaks them down into smaller, more manageable tasks. This detailed technical analysis and decomposition of work is a crucial step that promotes self-organization and fosters a shared understanding of the technical challenges and implementation approach among team members, reinforcing a sense of collective ownership over the Sprint’s objectives.

Finally, the Potentially Shippable Product Increment represents the sum of all the Product Backlog items completed during a Sprint and all previous Sprints. It is the tangible result of the development work and must be in a usable condition regardless of whether the Product Owner decides to release it. The concept of “Done” is central to the Increment; it represents a formal definition agreed upon by the Development Team and the Product Owner, serving as a checklist to ensure that all completed work meets the required level of quality, integration, and validation. Achieving a “potentially deliverable” state implies that the Increment is integrated, tested, and free of significant defects, meeting the agreed-upon Definition of Done, thus making it available for immediate release to stakeholders or customers at any time, at the discretion of the Product Owner.