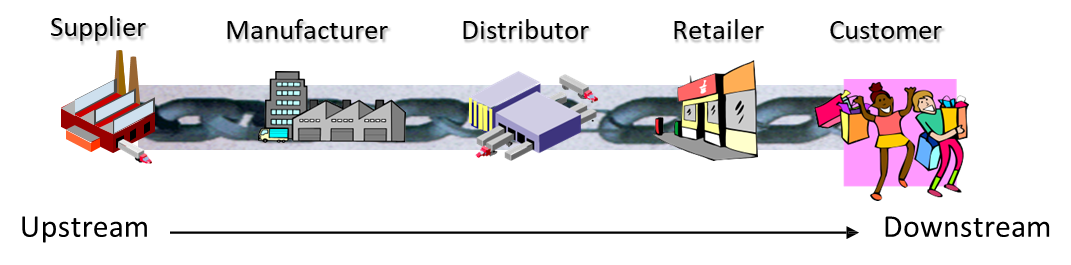

Supply chain management (SCM) revolves around the effective coordination of all activities involved in sourcing, production, and distribution, with the goal of delivering value to the end customer. At the heart of this process is the value chain, where raw materials and inputs enter on one side and finished products or services are delivered on the other. In recent decades, web-based information systems have introduced transformative capabilities to this value chain. One of the most significant innovations enabled by the internet is the possibility of establishing direct connections not only with clients but also with suppliers, creating a more integrated and responsive business ecosystem.

Initially, companies focused primarily on the client-facing (right) side of the value chain, using web applications to offer self-service solutions to consumers. However, over time—and often more slowly—they recognized the potential for integrating with suppliers (on the left side of the chain) to achieve a seamless flow of information and goods. Unlike client interactions, supplier integration required overcoming substantial technical barriers, especially concerning the interoperability of information systems across organizational boundaries.

The complexity arises from the fact that enterprise information systems, such as ERPs (Enterprise Resource Planning systems), are usually tailored to the specific operational and administrative needs of individual companies. Integrating such systems with those of external suppliers demands standardization efforts that are not trivial. This is particularly true for business-to-business (B2B) contexts, where companies operate at different stages of the value chain, each with unique systems, data formats, and operational requirements.

Self-Service in B2C and its Impact on Service Delivery

The evolution of self-service applications has played a central role in reshaping customer interaction within business-to-consumer (B2C) environments.

Example

A clear example of this transformation can be observed in the banking sector. Before the advent of electronic banking (e-banking), customers had to physically visit a branch to withdraw money, initiate transfers, or access financial services. This process was time-consuming and inconvenient, especially considering limited operating hours. With the introduction of online banking platforms, customers were empowered to perform many of these operations independently, from their personal devices and at any time.

However, the shift to self-service models comes with trade-offs. While users gain autonomy and save time, they also assume a greater degree of responsibility. Despite this, most people accept the self-service model due to the time efficiency and convenience it offers.

Nevertheless, not all services are equally suited to self-service. Simpler tasks like checking balances or making routine transfers are widely adopted. In contrast, more complex operations—such as selling investment funds or executing high-value transactions—are often subject to additional scrutiny and may even require approval from the bank. In such cases, the bank might contact the customer to confirm the operation and provide financial advice.

A significant source of complexity in B2B integration lies in the diversity of enterprise systems.

Example

Suppose Company

uses a particular ERP system to manage its inventory and purchasing operations, while Company —the supplier—uses a completely different ERP system. Each company defines its products, materials, and internal processes using proprietary codes, naming conventions, and data schemas. Over time, these systems become highly customized, with materials and products being encoded using logic and formats unique to each organization.

The process of ERP parameterization often takes many months and involves entire teams working to define material attributes, naming conventions, and classification codes. One common outcome is the creation of what are known as “cognitive codes,” or identifiers that are designed to convey descriptive information about a product. These codes are often long and complex, embedding features such as material type, color, and pattern within the code itself. While this approach helps internal staff quickly understand the nature of a product by reading its code, it also creates major integration issues when interacting with external systems that use different conventions.

Data Standardization and Structural Barriers in Supply Chains

The integration of supply chains is further complicated by the lack of universally accepted standards for coding products and materials. Since ERPs were originally designed for internal company use, they do not natively support the cross-organizational exchange of information unless significant effort is made to align coding systems. Each supplier in a network may use their own structure for product names, codes, and descriptors—making automatic data matching extremely difficult.

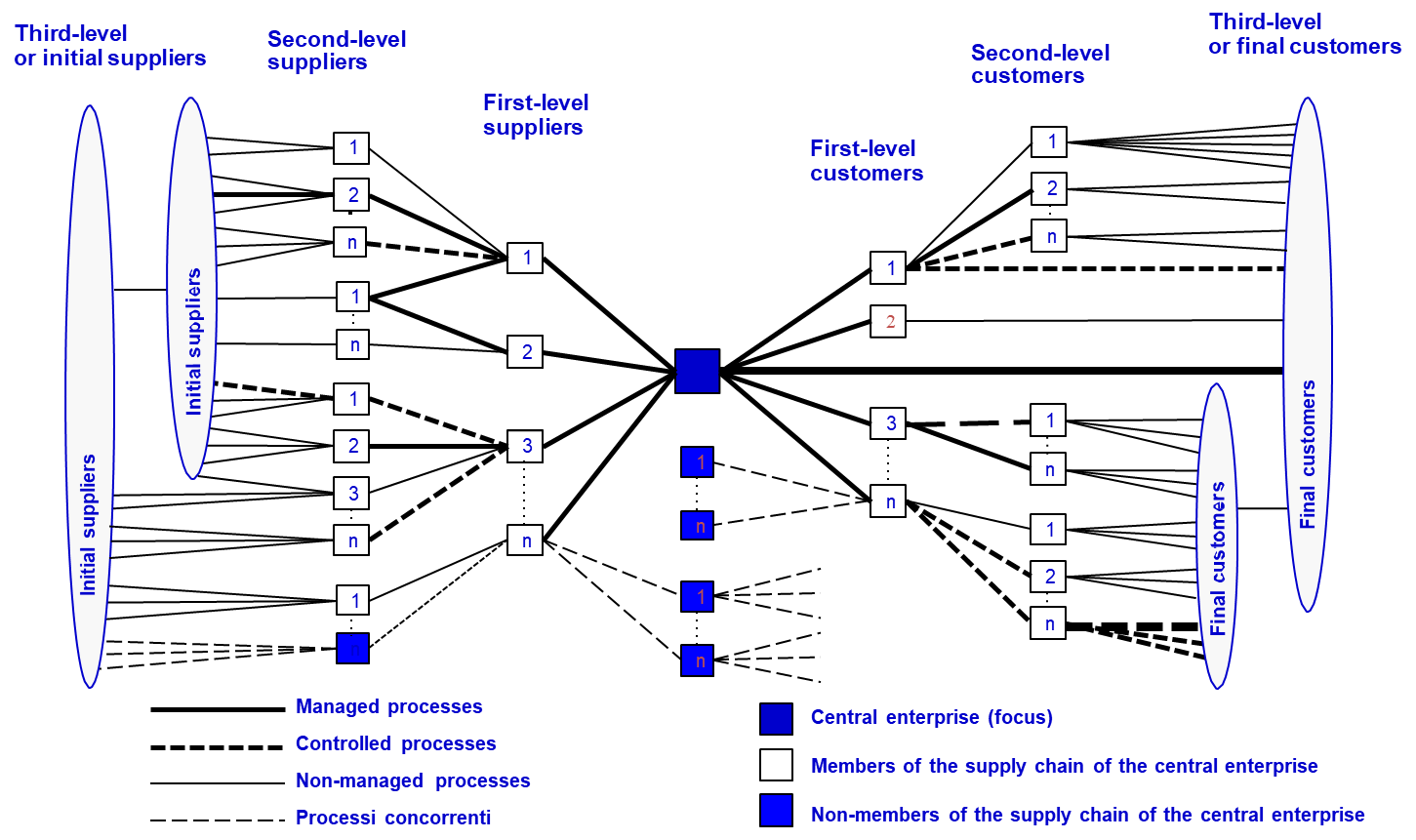

In larger supply chains, where a central company may coordinate with dozens or even hundreds of suppliers, this inconsistency in naming and coding leads to major inefficiencies. It becomes nearly impossible to automate procurement or inventory reconciliation without establishing a common data model or implementing robust translation layers between systems. Organizations may attempt to map different coding schemes manually, but this process is labor-intensive and error-prone.

Integration Challenges and Error Management

One of the most persistent and technically complex challenges in supply chain management (SCM) is achieving seamless integration across diverse systems. Even when organizations attempt to adopt universal coding standards, practical implementation often falls short. Although a universal product coding system might exist in theory, real-world variables such as new product introductions, smaller suppliers that haven’t yet adopted these standards, and legacy information systems continue to create inconsistencies in data formats and semantic interpretation.

From a technical standpoint, integration problems stem from heterogeneous systems trying to communicate using different protocols, naming conventions, and document formats. For instance, when a client requests an invoice, the assumption may be that the process is as simple as exchanging a document. However, in order for this to happen automatically—without manual intervention—both the sender and the receiver must adhere to the same structure for material codes, customer IDs, and transaction formats. Otherwise, automation becomes impossible or unreliable.

Defining SCM and its Value Proposition

Definition

Supply Chain Management (SCM) refers to a set of software tools, usually integrated as part of extended ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) systems, designed to coordinate and synchronize all activities across the value chain—from raw material sourcing to final product delivery. The primary objective of SCM is to reduce complexity and uncertainty by facilitating standardization, minimizing errors, and cutting down operational costs.

One of the major hurdles lies in the difficulty of establishing and enforcing a universal naming convention for products, services, and suppliers. A potential workaround is to adopt the same user-centric design that characterizes e-commerce platforms, where customers interact with supplier catalogs using standardized, self-service interfaces.

This supplier onboarding process requires suppliers to adopt the buyer’s system and follow strict protocols for order placement and delivery documentation. In large corporations, this integration is often mandatory. Suppliers must conform to the system requirements in order to be eligible for contracts. They submit their catalog data, accept automated ordering rules, and use the corporation’s software interface for dispatching goods and issuing invoices. This system of enforced integration ensures that orders are placed through predefined menus and dropdowns, eliminating the need for free-text input and significantly reducing data-entry errors.

For small and medium enterprises (SMEs), however, the adoption of such technology depends on the strength of the buyer–supplier relationship. If the buyer is a dominant market player, they may have the leverage to compel suppliers to go through the integration process. Otherwise, the cost and complexity of system alignment may discourage suppliers from participating.

The Ideal Vision vs. the Operational Reality

ERP vendors often present an idealized vision of SCM—one where fully integrated systems allow for perfect synchronization of supply and demand. In this utopia, companies receive the right products, at the right time, in the right quantities, and at the lowest possible cost, all while minimizing waste and maximizing customer satisfaction. While this vision is compelling, it overlooks the real-world complications of system integration and market fragmentation.

The reality is that supply chains are populated by a mix of strong and weak players. Dominant players can impose their coding schemes and process rules on smaller entities, but when multiple powerful actors are involved, standardization becomes a battleground. Each party may have its own set of standards and software protocols, and achieving consensus often requires negotiation, technical customization, and ongoing coordination.

Such fragmentation increases administrative burden and creates problems in financial reconciliation, tax compliance, and audit trails. From a systems integration perspective, the lack of a unified data model makes end-to-end automation elusive, particularly when dealing with global suppliers who operate under various regulatory and technological constraints.

Overcoming Demand Uncertainty

A core motivation for investing in SCM technology is to better manage demand uncertainty. Businesses operate under continuous pressure to forecast customer demand and align their operations accordingly. Misjudging demand has significant repercussions: underestimation results in missed sales opportunities and customer dissatisfaction, while overestimation leads to excess inventory and financial losses.

To navigate these challenges, firms aim to build more responsive and flexible supply chains. This is where SCM’s value proposition becomes critical. By integrating suppliers into internal planning processes, companies can enhance their responsiveness to unexpected market fluctuations.

- If demand suddenly spikes, a well-integrated supplier can rapidly adjust their production and delivery schedules.

- If demand drops, integrated systems can facilitate order cancellations or modifications before production begins—saving both time and money.

In this context, integration is not merely about transaction automation. It is about enabling dynamic collaboration between buyers and suppliers, often referred to as collaborative planning or concurrent engineering. Suppliers become partners in the design and forecasting process.

Objectives of Supply Chain Management (SCM)

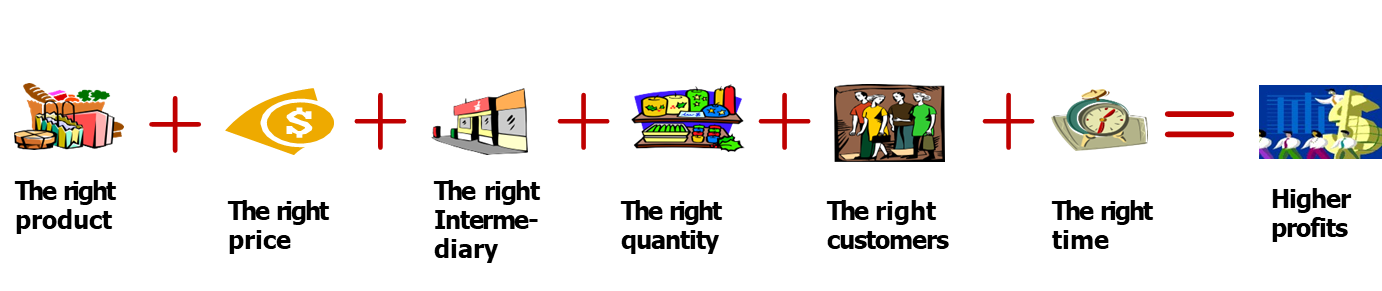

Once a company has achieved a certain level of integration across its operations and partners, the discussion naturally shifts from what integration means to why it matters. At this point, the focus is no longer on understanding the concept of integration in abstract terms, but on appreciating its role in delivering measurable value to the business. In professional environments, it is common to hear suppliers claim that their goal is to provide “the right product at the right time.” While this statement may sound like marketing rhetoric, it actually reflects a fundamental operational objective in supply chain strategy.

Behind this slogan lies a set of complex, practical requirements that organizations must fulfill to realize such a promise. Achieving the “right product at the right time” demands more than efficient logistics; it requires seamless coordination between demand forecasting, inventory management, supplier reliability, production planning, and data-driven decision-making. In technical terms, the supply chain must be capable of synchronizing inbound and outbound flows with minimal latency and high adaptability.

Inter-Firm Relationships within SCM

Once a company has established the ability to evaluate, control, and monitor its supplier network, it can begin to strategically manage its relationships based on performance metrics.

The goal at this stage is not just to know who the best suppliers are, but to cultivate strong partnerships with those that provide the most value. Ideally, high-performing suppliers should be encouraged to prioritize the company over other clients.

While exclusivity may not always be realistic, fostering loyalty and collaboration is both desirable and achievable.

To develop this kind of relationship, companies must engage in long-term relational management. This involves treating suppliers not as transactional entities but as strategic partners. One common approach is to involve key suppliers in the company’s growth narrative. When suppliers perceive that they are contributing to a dynamic and expanding business, they are more likely to commit resources, offer better service levels, and align their priorities with those of the buyer.

This deeper form of collaboration often begins with requirements management, a process that goes beyond transactional exchanges such as order placement, delivery, and invoicing. In advanced supply chains, the supplier is engaged from the early stages of product and service development. Rather than simply responding to purchase orders, suppliers participate in co-design activities, where specifications, functions, and performance criteria are defined collaboratively, transforming the supplier-buyer interaction into a continuous cycle of innovation, adaptation, and shared risk.

In technical terms, this means that suppliers must be prepared to contribute not only manufacturing capabilities but also R&D resources, engineering input, and planning alignment. The model moves toward concurrent engineering and extended MRP (Material Requirements Planning), where production plans and development cycles are no longer siloed within a single organization. Instead, the supplier operates as a tightly integrated node within the buyer’s operational ecosystem. This level of integration allows both parties to reduce time-to-market, minimize inventory buffers, and respond more effectively to changes in customer demand.

The Strategic Focus on Key Suppliers

The initial and most critical step in developing such high-level SCM integration is to identify and focus on the most important suppliers. Not all suppliers will have the capacity, willingness, or strategic fit to engage in such deep collaboration. Therefore, companies must prioritize those that contribute to core business operations, offer innovative capabilities, or represent long-term value.

Once these strategic suppliers are identified, companies can begin to invest in shared systems, collaborative platforms, and joint development programs. This is not an improvised process—it requires planning, resource allocation, and governance mechanisms to manage inter-organizational complexity. Integration at this level also assumes that both parties have compatible IT architectures, mutually agreed standards, and a strong foundation of trust. Without these, even the most well-intentioned partnerships can collapse under the weight of operational misalignment.

SCM Learning Process

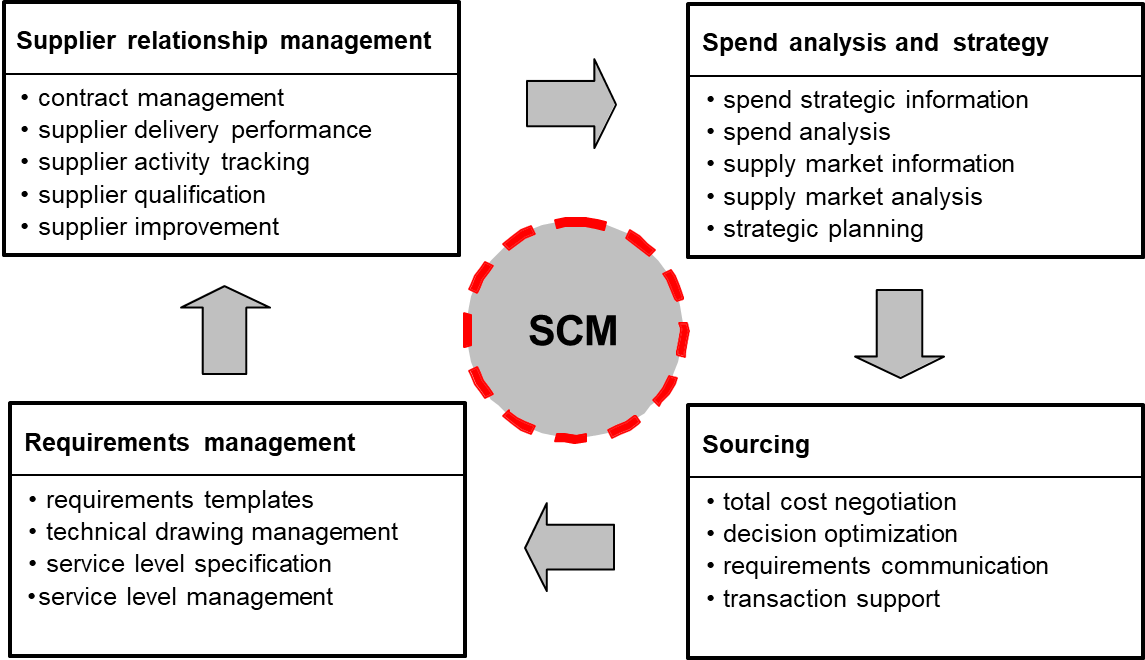

In the context of Supply Chain Management (SCM), continuous improvement and learning are essential for maintaining competitiveness and operational efficiency. Effective supply chain strategy begins with a thorough understanding of how and where financial resources are allocated in the procurement process. This is where spend analysis plays a foundational role, guiding decision-makers in aligning purchasing strategies with organizational goals.

Step 1: Spend Analysis and Strategic Assessment

The journey towards supply chain optimization begins with a spend analysis, a data-driven method to evaluate how much the organization is spending, what it is spending on, and with whom.

A standard approach is to classify all purchased goods, raw materials, and services based on total annual expenditure. When sorted by descending order of value, this often reveals a Pareto distribution—commonly referred to as the 80/20 rule. In practical terms, this means that roughly 20% of procurement items typically account for about 80% of total spending. These high-spend categories are often strategic commodities or services and thus should become the primary focus of optimization initiatives.

Once these critical items are identified, it becomes essential to analyze the characteristics of the suppliers who provide them. This comparison helps determine whether the organization is overpaying or under-leveraging its position in supplier negotiations.

If, for example, a significant portion of spending is concentrated with a single supplier, this could indicate a risk of dependency or reduced bargaining power. Even if the supplier is currently reliable, it is generally more desirable to have alternatives to avoid being locked into a monopolistic relationship. This motivates the need for market analysis, conducted through both qualitative and quantitative research. Sources might include public databases, industry white papers, analyst reports (such as Gartner or IDC), and procurement intelligence platforms.

Step 2: Strategic Sourcing and Supplier Optimization

Following spend and market analysis, the organization enters the sourcing phase, which involves refining the supplier base to ensure cost-effectiveness, quality, and supply chain resilience. This step includes negotiating better pricing, re-evaluating existing supplier contracts, and potentially onboarding new suppliers to reduce risk and increase competition.

A key objective of sourcing is supplier diversification—moving from a single-source model to a multi-source strategy whenever feasible. Introducing two or more suppliers for a critical component or service reduces dependency, enhances flexibility, and stimulates performance improvements through competition. Newly added suppliers must be carefully integrated into operational processes and subjected to performance evaluations over time.

Supplier evaluation is an essential aspect of strategic sourcing. It involves assessing suppliers based on multiple performance criteria:

- Delivery lead times

- Pricing competitiveness

- Product or service quality

This is where the concept of end-to-end traceability becomes critical. To assign responsibility for recurring product failures, organizations must be able to trace defective components or services back to the originating supplier. This requires robust integration across enterprise systems, particularly those handling field service management, inventory, and procurement.

Example

For example, in a fully integrated system, a defective washing machine installed at a customer’s home can be traced back through production records to the specific parts used, the suppliers who provided them, and even the batch number. Such traceability ensures that, in the event of failure, root cause analysis can identify whether a pattern exists pointing to a particular supplier.

Step 3. Requirements Management

Requirements management is a fundamental process within modern supply chain and product development practices. It involves the systematic handling of requirements throughout a product’s lifecycle, from the initial research and development phase to final delivery and beyond.

The goal is to ensure that all stakeholders — including internal departments and external suppliers — are aligned on what needs to be delivered, how, and under which conditions.

In today’s collaborative environments, requirements management is no longer a linear or isolated activity; it is deeply integrated into the co-design and co-development of products and services. The process starts as early as the research and development (R&D) phase, where companies and their suppliers collaborate on conceptualizing solutions that meet emerging market or customer needs.

This integration requires suppliers to not merely provide components but to actively participate in the design and engineering phases. This approach, often referred to as concurrent engineering, enables both parties to iterate over designs, align on technical specifications, and address potential constraints proactively. By working together from the beginning, organizations and suppliers build a shared understanding and technical vocabulary. They define product characteristics, component names, and performance requirements in a way that eliminates ambiguity, fosters smoother collaboration, and accelerates development. Such synergy is vital when dealing with customized solutions or made-to-order products, especially in industries with high variability in customer demand.

However, requirements management is not a one-off task. It is an ongoing, cyclical process that must be revisited and revised over time. Markets evolve, technologies change, and suppliers may come and go. Therefore, it is essential to maintain the adaptability to revise requirements, onboard new partners, and ensure continuity without compromising product quality or time-to-market goals.

Step 4. Supplier Relationship Management

Supplier Relationship Management (SRM) is the strategic practice of managing interactions with organizations that supply goods or services. The objective of SRM is not only to ensure the continuity and reliability of supply but also to cultivate strong, value-driven relationships that contribute to innovation, flexibility, and competitive advantage.

One of the key challenges in SRM is the potential loss of high-performing suppliers. This loss may result from external disruptions, strategic shifts, or operational issues. To mitigate the impact of such changes, companies must institutionalize the knowledge and best practices developed during their collaboration with previous suppliers. This knowledge transfer becomes the foundation for training and integrating new suppliers into the company’s ecosystem.

To ensure a smooth onboarding process, organizations implement structured programs such as supplier certification, technical training, and qualification procedures. These initiatives aim to reduce the time required for new suppliers to reach optimal performance levels. Moreover, companies often invest in supplier development programs, designed to enhance the capabilities of smaller or less experienced suppliers, allowing them to scale up and eventually take over complex tasks such as design ownership, prototyping, or maintenance.

From a startup perspective, establishing a relationship with a large corporation can be particularly challenging. Positioning the company in an area that aligns with the client’s unmet needs — especially in innovative or unexplored domains — is often the best entry strategy. Big companies frequently face internal inertia or lack the agility to develop entirely new solutions. This is where startups can provide value: by offering flexible, niche solutions with faster development cycles and lower overhead. Once a relationship begins, the startup typically needs to adapt to the larger company’s processes and standards. Over time, mutual trust and familiarity grow, creating a shared language and reducing barriers to communication.

Final Considerations

It is crucial to understand that supply chain management is not merely a technological issue. While automation, data exchange platforms, and ERP systems are essential tools, the real complexity lies in organizational transformation. Both the company and its suppliers must evolve their coordination mechanisms, workflows, and culture to become more responsive to shifting market demands.

This transformation often begins with a pressing pain point, such as inefficiencies in procurement or errors in invoicing. These practical issues become the catalyst for broader change. Although the initial motivation may be to eliminate inefficiencies, the long-term benefit is the creation of a more resilient, adaptable, and innovative supply chain network.

Ultimately, success in modern supply chain management depends on a company’s ability to treat its suppliers as partners, not just vendors. Through integrated development, knowledge sharing, and mutual growth, organizations can build a supply chain that is not only cost-efficient but also strategically aligned with future goals. This capability is increasingly recognized as a key competitive differentiator in today’s dynamic and complex business environment.